„Mossy green traces of plants that once grew tall draw their lines on the black, undulating exterior wall of the Simultanhalle.* Its statics seem to be holding on tightly to the aluminium-like plasters with which some parts of the wall have been repaired. A temporary solution – now in the process of decay. Some are watching it with concern, while others are waiting impatiently.

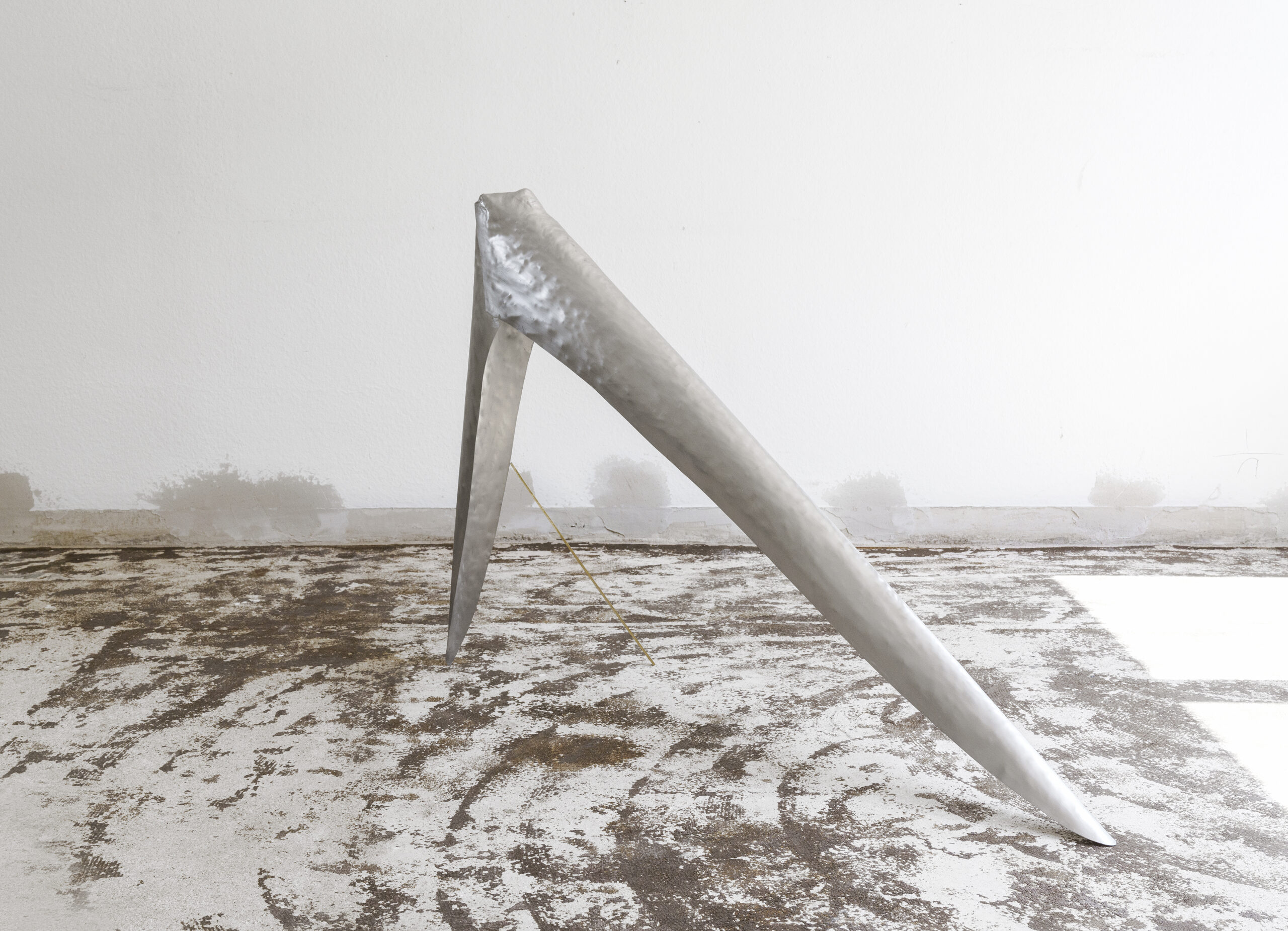

Visible and yet hidden, in the sprawling green of the surrounding bushes and trees, in front of the black exterior wall of the building, a three-metre-high figure shimmers metallically: Two conical, semicircular aluminium funnels with their openings facing each other. On their surfaces, both inside and out, the surroundings appear in distorted reflections. In their statics and size, they seem to give way to fluidity in the play of light and shadow, almost dissolving into it. The space between them and their diameter alone is just wide enough to accommodate a medium-sized body.** Do they serve here as a shelter, a shield or even as a monumental mouthpiece?

From beneath the large metallic figure, from the green of the surrounding bushes and the exterior wall of the building, black soil pours into the courtyard. Soft on the first step – leaves marks, hardens with repeated steps. As a material and habitat in which new life continually emerges from the processes of decay: Black Soil. A stranger here, at home there. A place where territorial borders and affiliations are negotiated: Black Soil. Where we came from, where we go and what we become. Loosely thrown hints do not help with orientation and localisation – on the contrary, a confusion spreads through history(s).“

In „songs of conditions“, Olga Holzschuh creates an installative embodiment of quiet melancholy, in which the political and the personal intermingle through questions of loss, emptiness, belonging and the dealing with it.

The performative reading on 14th of September, due to the finissage of Simultanhallenprojekte 2024, offers further insights into the work’s multiple layers.

EXHIBITION: 1.6 – 14.9.2024 / Simultanhalle, Volkhovener Weg 209, 50765 Cologne (Germany)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*Built in 1979, the building was originally intended as an architectural model/test building for the new Museum Ludwig in Cologne city centre. When the project was completed in 1983, the temporary building was to be demolished.

**cf. Patrizia Dander, „Feeling blue“, in: hold on, Olga Holzschuh, Distanz Publisher, 2023

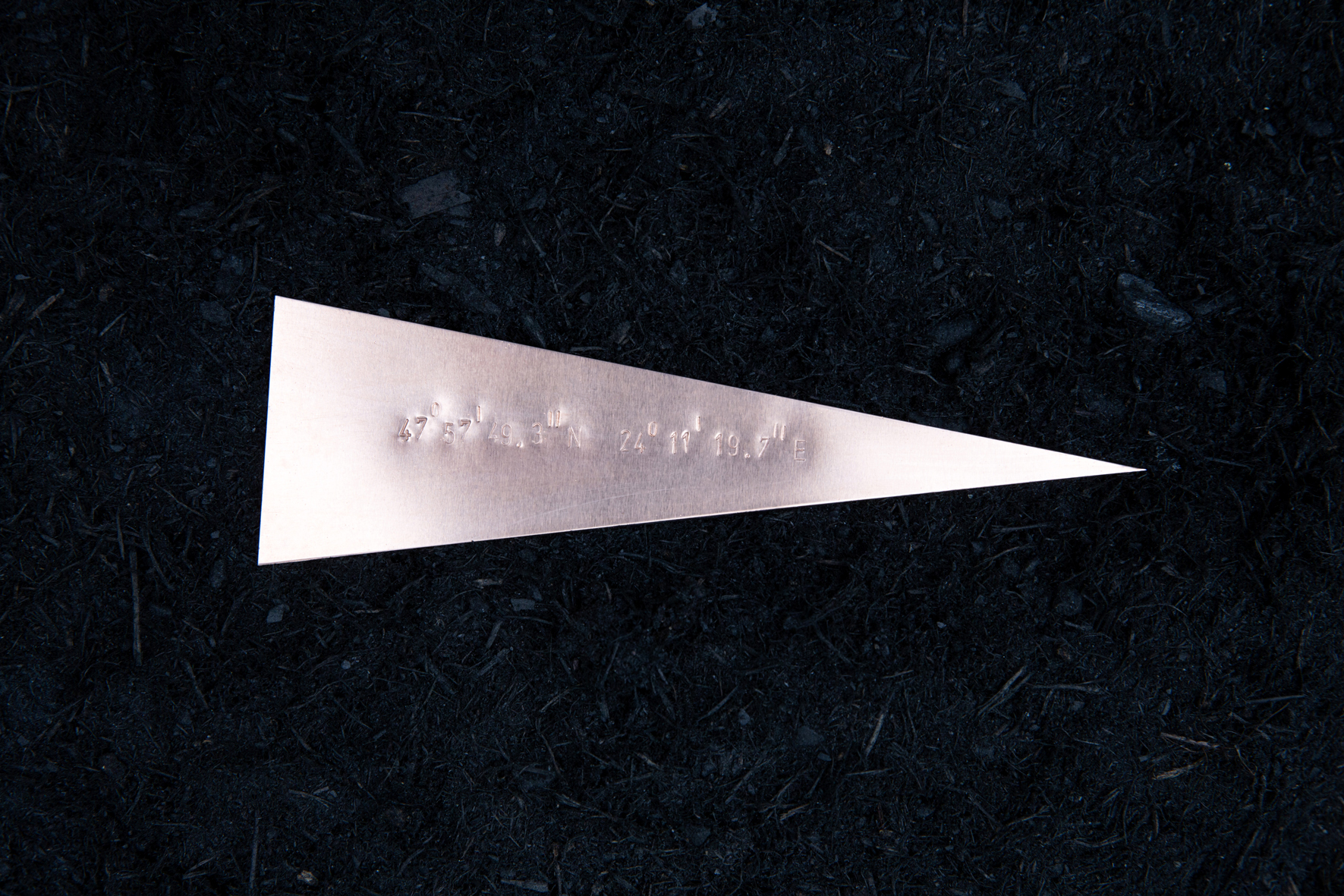

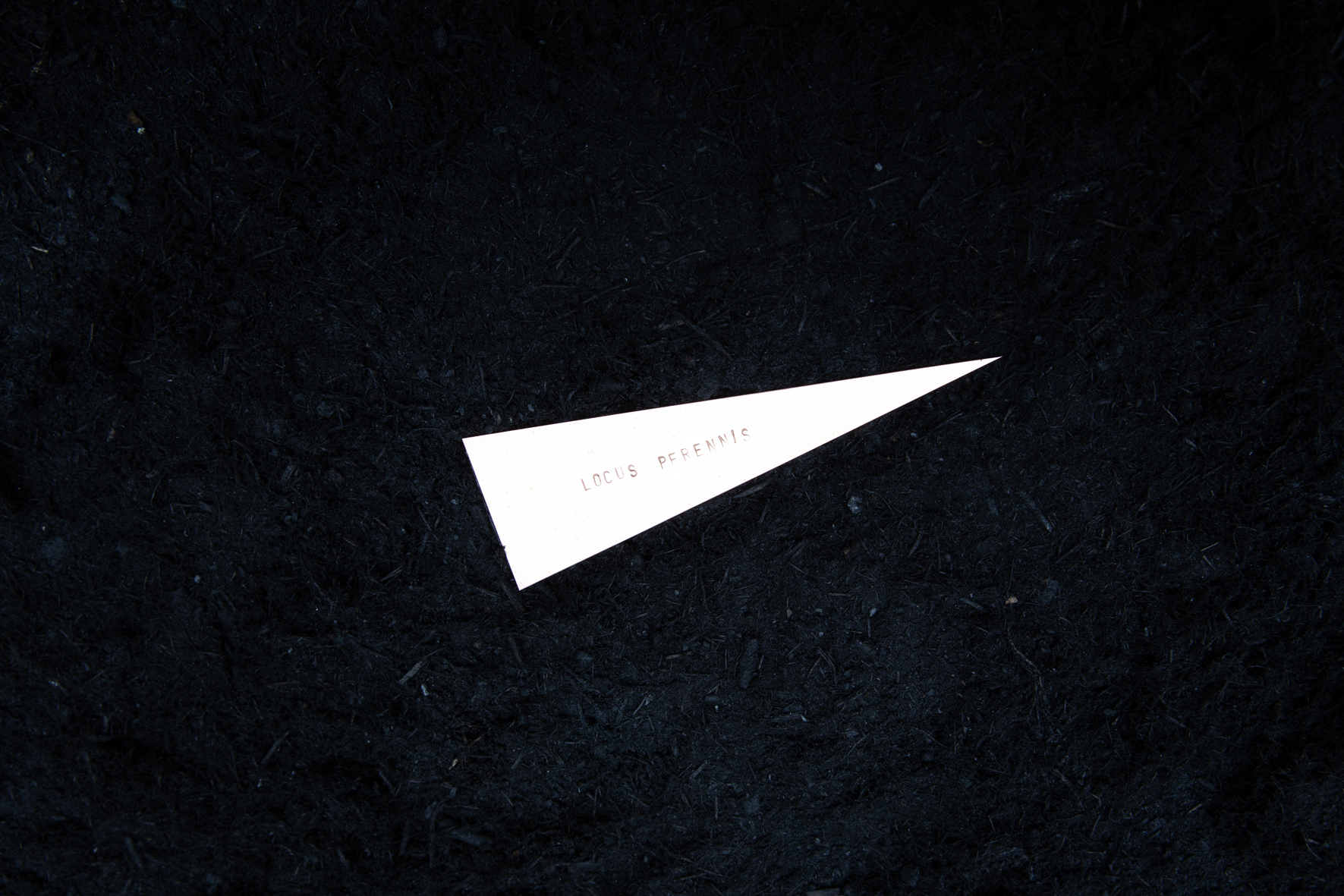

Work details:

songs of conditions, 2024

Black soil, aluminium, copper

Installation: dimensions variable,

aluminium sculptures: 2-pcs. / each 300 x 70 x 35 cm,

copper objects: 4 – pcs. variable size, max. 25 x 10 cm

All copper objects pointing to the East.

They point the way to the geographical centre of Europe (once in the Transcarpathian region of present-day western Ukraine)

& to the largest deposit of black soil.

untitled (3640 mm) / Vibrant Waters

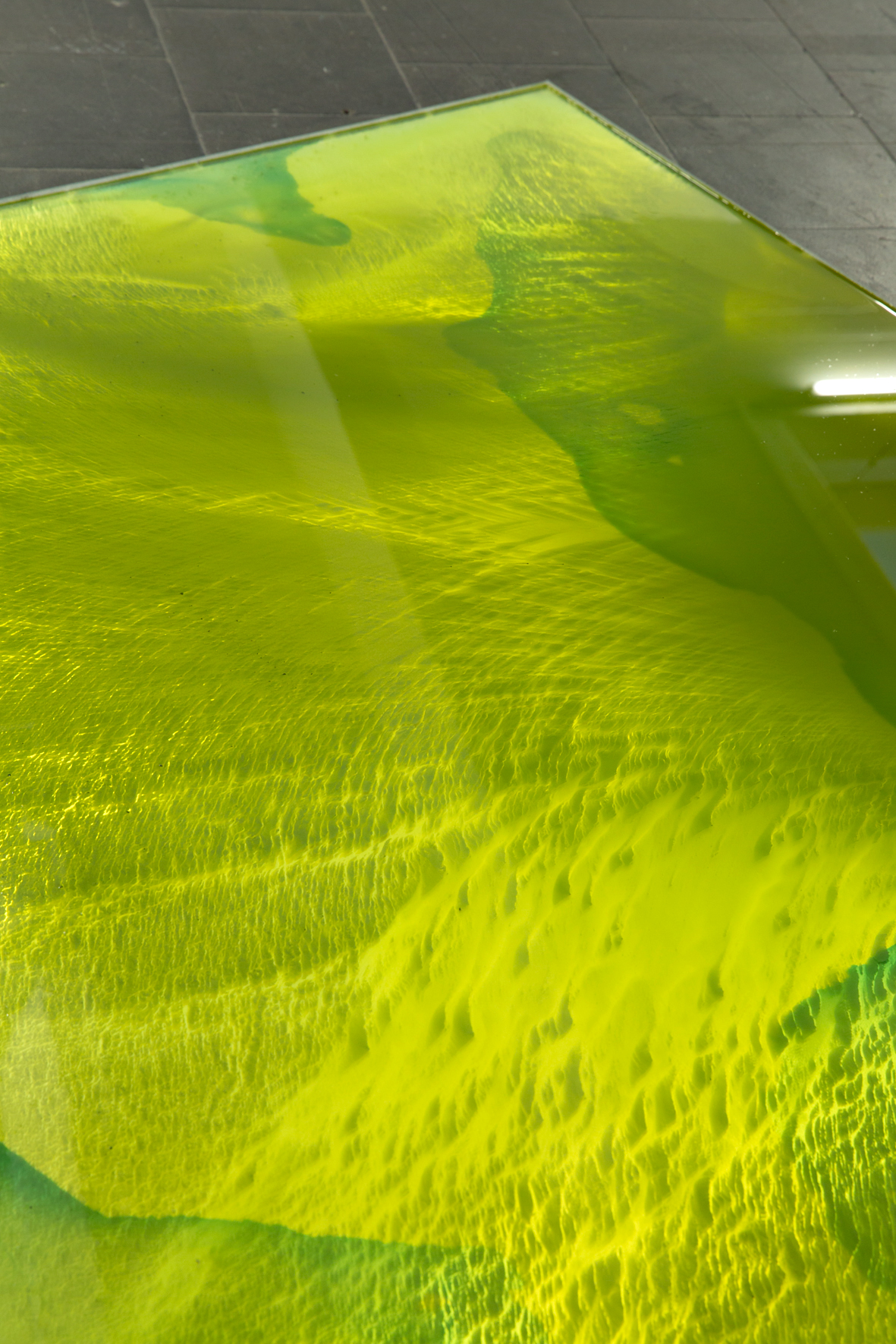

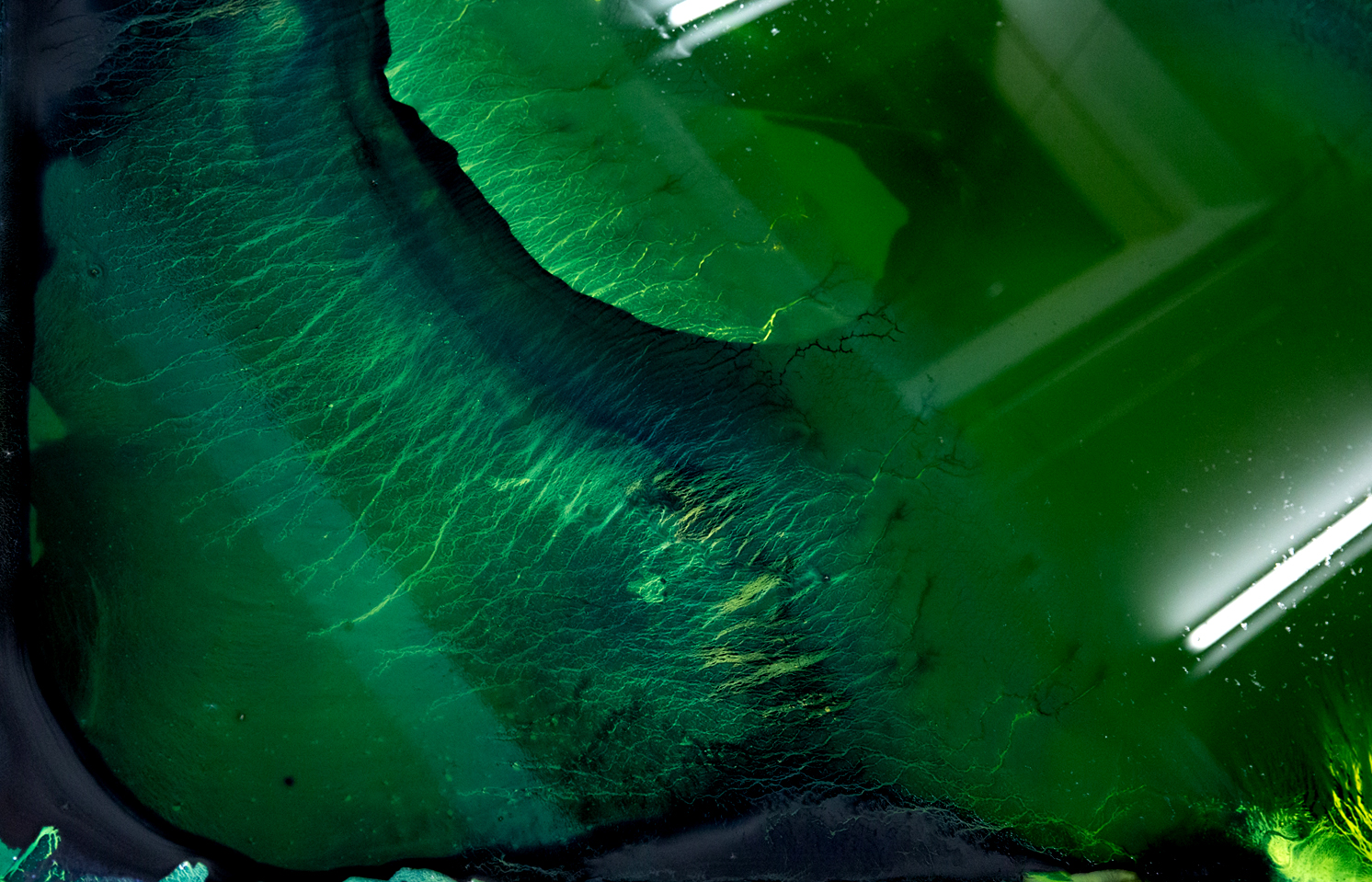

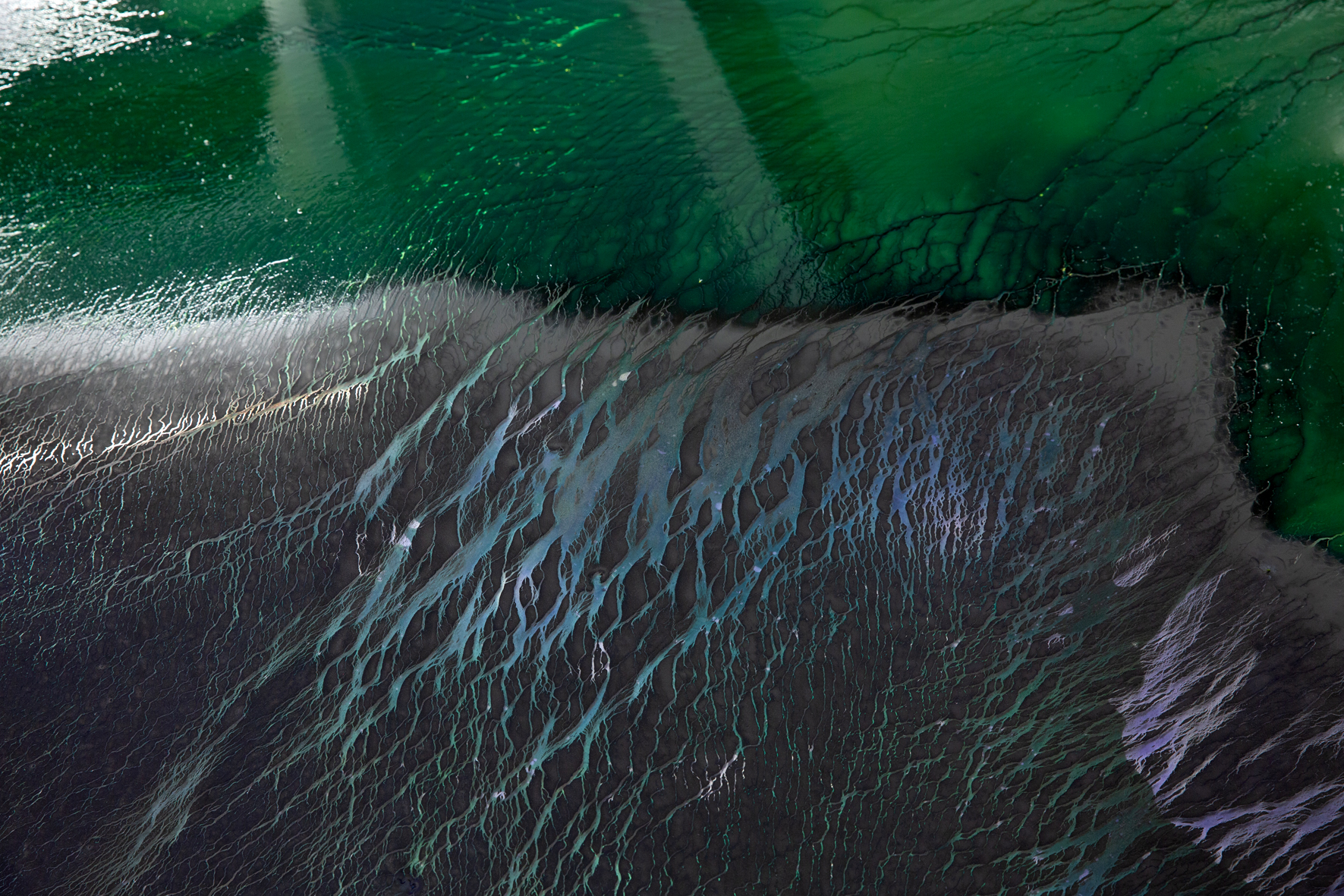

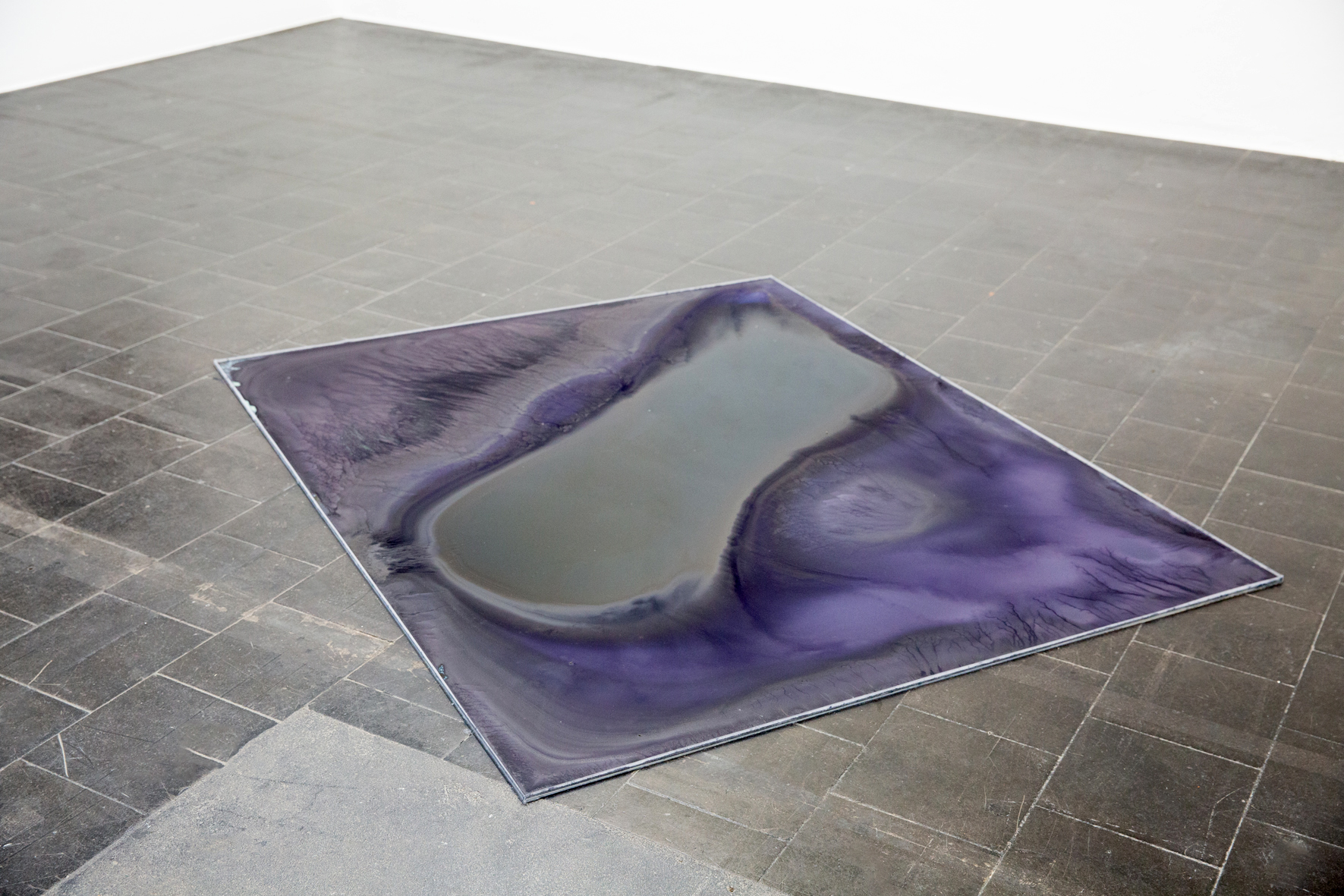

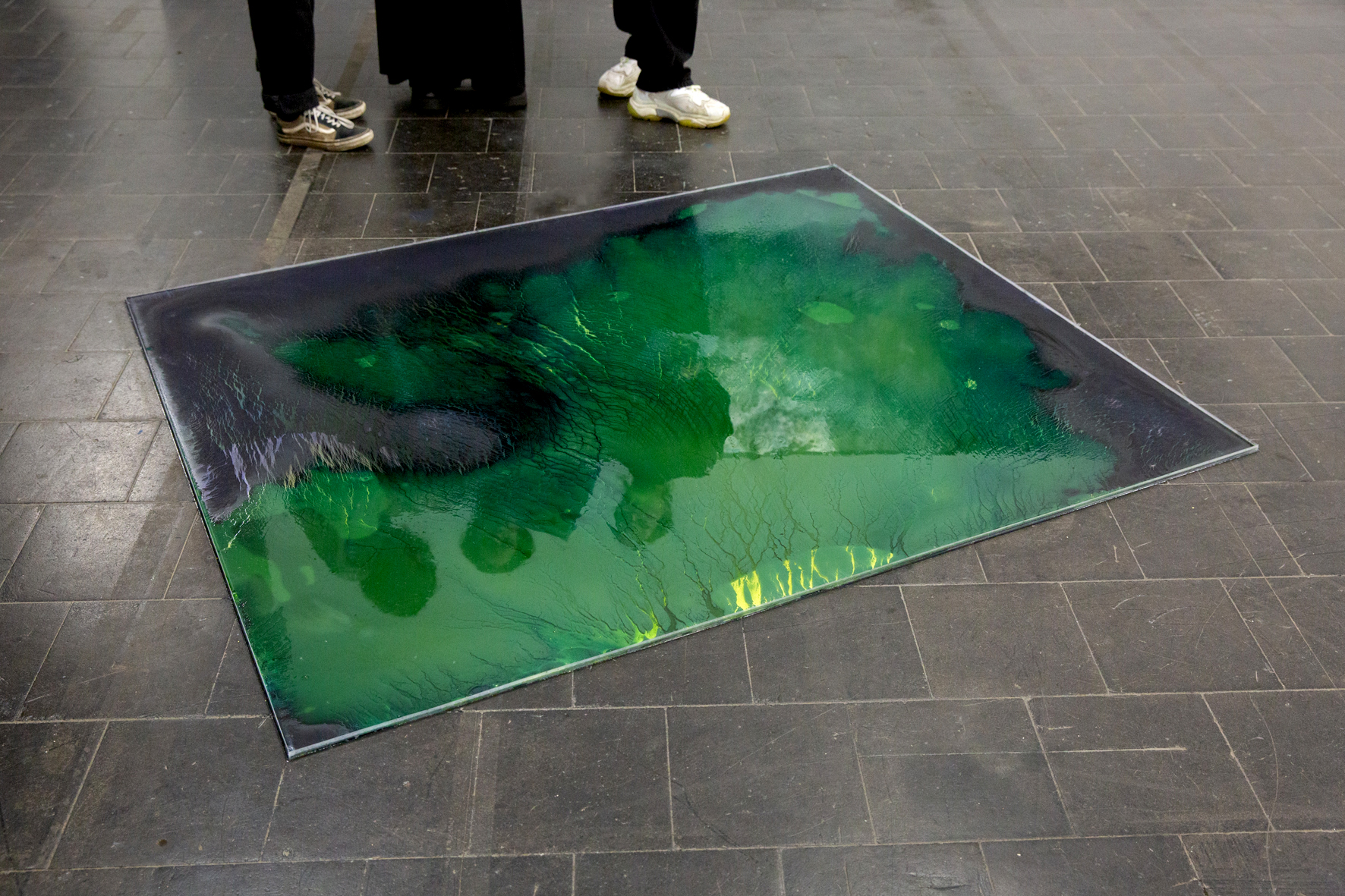

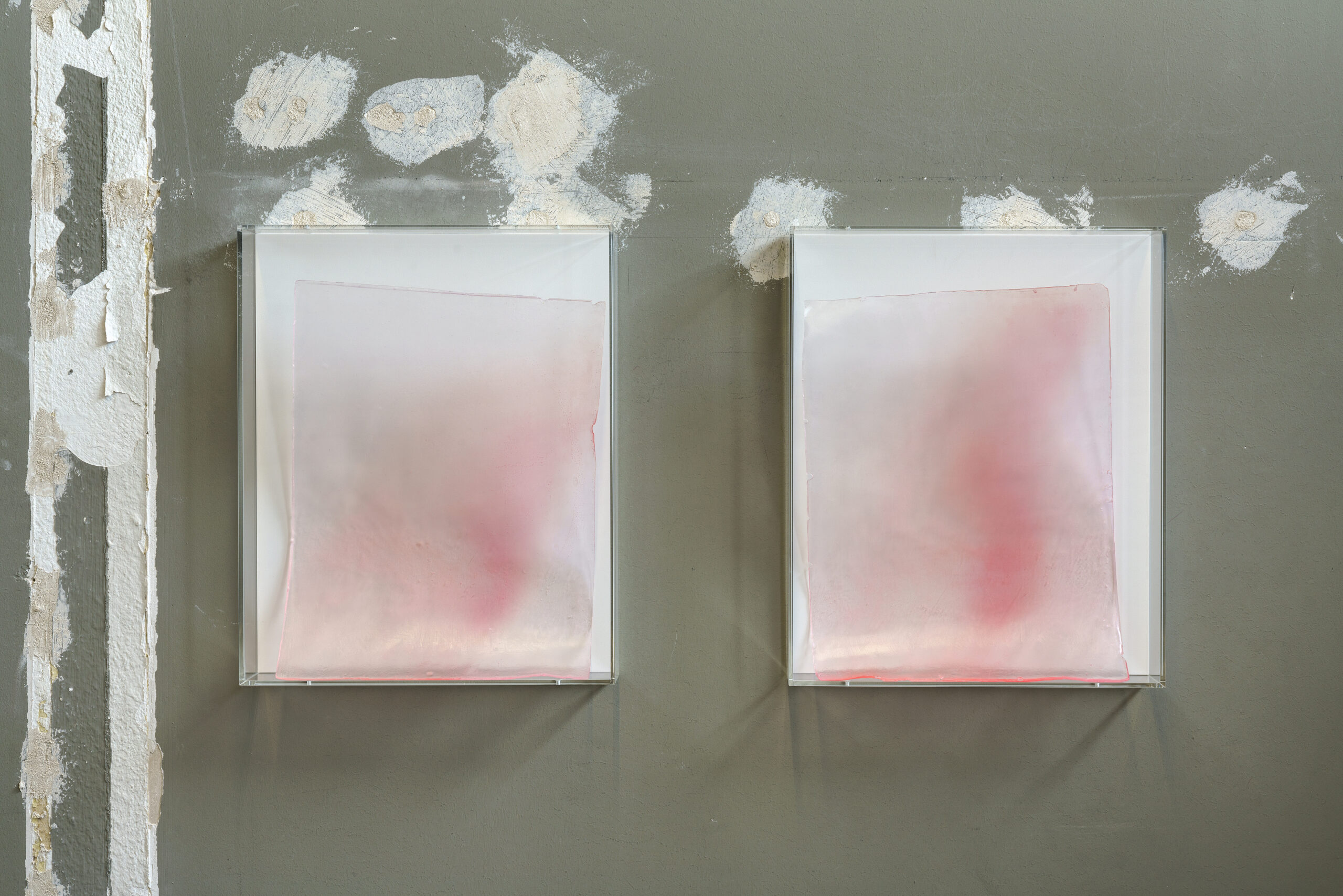

Water and light are not only the basis of all life on earth, they are also indispensa-ble to the human perceptual apparatus and form the material foundations of photography. To make the role of the two elements in the imaging process visible, the artist Olga Holzschuh works with cyanotype: iron and salt-containing powders are mixed with water to form a light-sensitive emulsion.

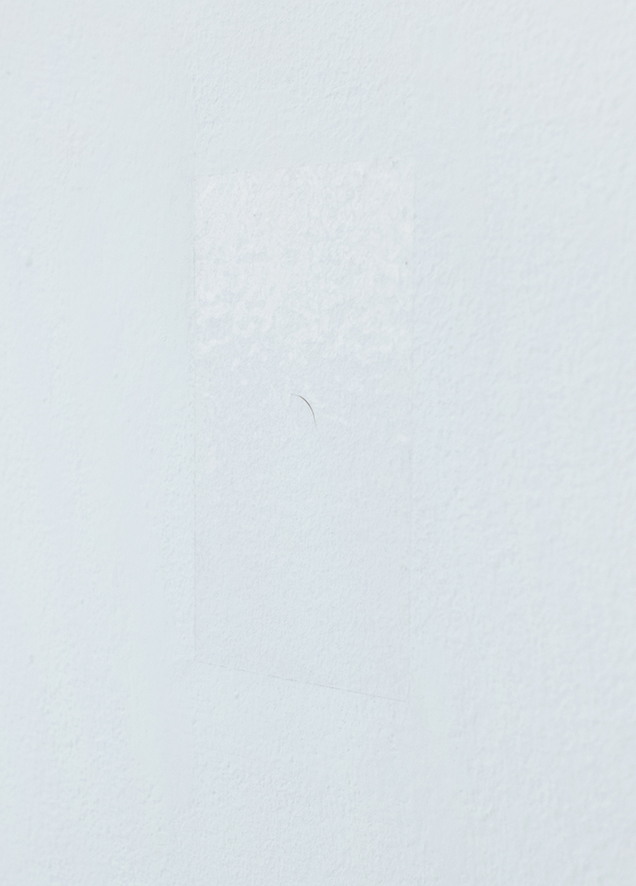

For the work o. T. ( 3640 mm ) Holzschuh applied the cyanotype to three glass plates. The dimensions correspond to the size of the ceiling windows of Temporary Gallery. The water for the solution was taken from the Rhine and was used unfil-tered. River water and light incidence allow for an indexical tracing that intertwines two places and ecosystems.

Both the water of the river and the incidence of light in the room carry site-spe-cific information. H2O occurs outside the lab only in conjunction with other constit-uents that reveal something about the history and current state of the body of water. In parallel, the architecture and the presence of bodies in the space deter-mine the way in which light is reflected, refracted or absorbed in contact with matter. As the moisture slowly escapes from the emulsion, this information in-scribes itself into the image carrier. The artist deliberately omits the final step of fixing the motifs. The process is finished as soon as the surface dries out and becomes porous.

The cyanotypes created in the exhibition space can be seen as a poetic commentary on the fragility and ephemerality of spatiotemporal constellations, which also include (eco)systems. Against the backdrop of the exhibition’s themat-ic setting, Olga Holzschuh’s work takes on a darker note: what is at stake when water retreats from the landscape?

Nada Rosa Schroer

untitled (3640 mm)

Glass, aluminum, water, potassium hexacyanidoferrate, ammonium iron citrate

142 x 172 cm, 3-piece, 2023

Content:

„Vibrant Waters“ Exhibition curated by Nada Rosa Schroer at the Temporary Gallery, Cologne (Photoscene Co-Labs),2023

At a time when lakes are drying up, rivers are disappearing, and groundwater resources are diminishing due to overuse and climate change, the question of water is of the utmost urgency.

Against this backdrop, the exhibition Vibrant Waters traces the qualities of the element. If we were to pay attention to water, what would it tell us? On view are artistic positions that question the understanding of the element as an abstract raw material and, in doing so, examine the material conditions of imaging practices. What is the relationship of water to the production and circulation of images? How do watery relations become visible in images and how can modes of production and relations be counter-read from a hydrofeminist and decolonial perspective?

From both historical and contemporary perspectives, water is fundamental to image production. It is needed in large quantities for the extraction of metals, precious metals, and rare earths, as well as used in the semiconductor industry and for cooling server farms. Both the extraction of raw materials and the produc-tion of the media supporting images inscribe themselves on waterscapes. What do these landscapes tell us about the power relations and hierarchies within dominant and Western worldviews, in which the conceptual separation of “nature” and

“culture” allows the environment to be exploited as a cheap material?

Water is much more than a raw material that can be reduced to the abstract formula H2O. In many non-Western indigenous cosmologies, the liveliness of all matter is fundamental to understanding interconnectedness. “Water is relation,” is how Anishinabe scholar Deborah Mc Gregor puts it. Water forms living bodies that permeate everything and create the conditions for the all living. The plural of the English word in the title of the exhibition refers to the innumerable forms, composi-tions and cycles in which the wet and liquid manifest themselves on earth and sub-tly connect different bodies – from the microscopic level of a cell to the macro-scopic level of planetary weather phenomena. “As watery,” philosopher Astrida Neimanis describes it, “we experience ourselves less as isolated entities, and more as oceanic eddies: I am a singular, dynamic whorl dissolving in a complex, fluid circulation.”

The Vibrant Waters exhibition explores how water cycles continue through medium, body, environment, and society, and explores how aqueous interdepend-encies are expressed artistically. Many of the positions presented in the exhibition relate to contexts shaped by extractivism, capitalism, and colonialism. They point to water as a shaper of economic, political, and spiritual relationships, as a carrier of information, or as an aesthetic agent that creates images of itself. They docu-ment how communities come together at the waterside in resistance to the loss of their livelihoods, or speculate about posthuman beings watching over toxic waters in the ruins of the Capitalocene.

unburnt wet clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 20x20x8cm

unburnt wet clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 20x20x8cm

untitled (48°32'27.0 "N 22°59'40.7"E) glycerine soap, transfer print (photography), plexiglas, 43x54x6cm

untitled (48°32'27.0 "N 22°59'40.7"E) glycerine soap, transfer print (photography), plexiglas, 43x54x6cm

Aluminium sculpture, each 300x70x35cm

Aluminium sculpture, each 300x70x35cm

unburnt wet clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 110x47x7cm

unburnt wet clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 110x47x7cm

unburnt dries clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 110x47x7cm

unburnt dries clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 110x47x7cm

cyanotype wall, aluminium rods, 500x800x100cm

cyanotype wall, aluminium rods, 500x800x100cm

unburnt dried clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 20x20x8cm

unburnt dried clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 20x20x8cm

unburnt dried clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 70x33x5cm

unburnt dried clay, Matyó embroidery (imprint), 70x33x5cm

EN

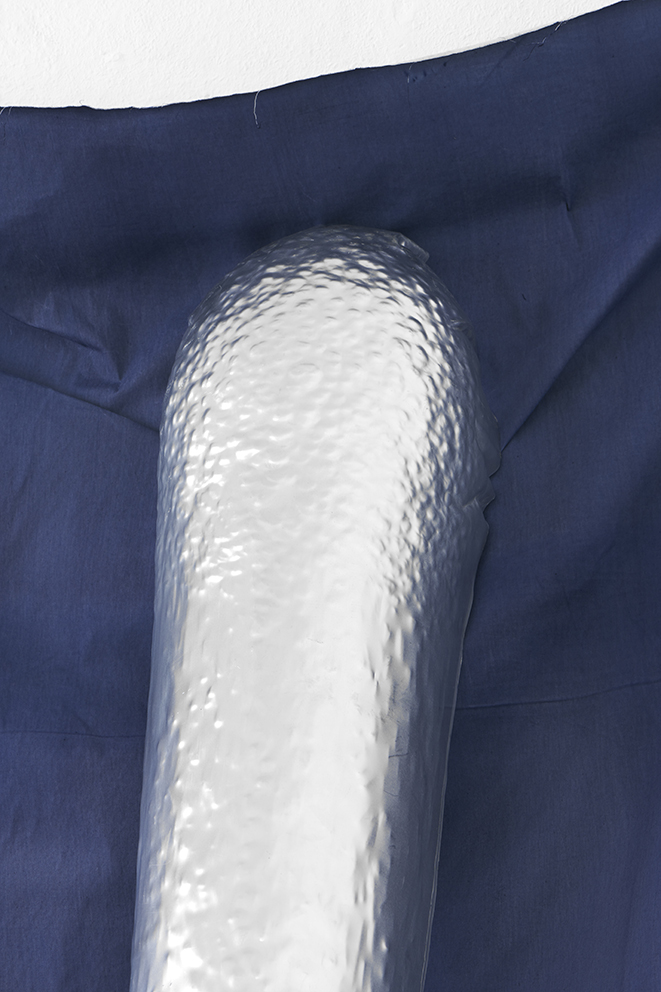

hide and seek is a site-specific installation by Olga Holzschuh. One wall of the Kunsthalle is coated with a UV-sensitive emulsion that reacts to daylight, capturing it and, in an evolving process of many hours, bathes the affected surface in a nuanced blue. Cyanotype – one of the oldest photographic processes for creating and fixing images – allows traces and layers of earlier wall treatments to shine through and form an immediate connection with another element of the installation: the fragile aluminum scaffolding penetrating the wall horizontally, like a cannula, and reaching up vertically into the Kunsthalle ceiling. The façade of the house in which the artist spent a good part of her childhood served as a model for the sketchy construction. The memory of places left behind is a unifying element that appears in several of her works. This is also the case in the photograph untitled (48°32’27.0 „N 22°59’40.7 „E), made of soap using the transfer print process developed by the artist. As if under a transparent layer of skin, the material conceals the image of the house of her childhood, like the fading memory image conceived in the attempt to capture. The desire to preserve or conserve through photography or cyanotype and at the same time the realization of loss and emptiness mark a dialectic that is reflected in the stability and instability of the provisional architecture as well as in the evaluation of security and danger, which takes place through an audible signal in Olga Holzschuh’s sound work. Since the 14th century, a horn signal has sounded from the tower of the St. Lamberti Church in Münster as a sign of safety and peace – blown by a:n Türmer:in (currently by the Türmerin Martje Thalmann). However, the signal sounds only in the directions of the south, west and north. The east has always been left out. The fragile house construct of Olga Holzschuh’s installation is located in the east of the Kunsthalle. Opposite it are three large sculptures, bent in the form of hollow cones made of aluminum. Distributed in the room, they mark the three cardinal directions mentioned above: South, West and North. More than three meters high, they are reminiscent of monumental mouthpieces, archaic-sounding in-struments, or even large shields predestined for hiding. Every half an hour, the horn signal of the Türmerin resounds in the midst of the installation, alternating between warning and security.

DE

hide and seek ist eine ortsspezifische Installation von Olga Holzschuh. Für diese wurde eine der Wände mit einer UV-sensitiven Emulsion bestrichen, die auf das Tageslicht in der Kunsthalle reagiert, dieses einfängt und in einem stundenlangen Entwicklungsprozess die betroffene Fläche in ein nuanciertes Blau taucht. Die Cyanotypie – eines der ältesten fotografischen Verfahren zur Herstellung und Fixierung von Bildern – lässt Spuren und Schichten früherer Wandbearbeitungen durchscheinen. Das fragile Aluminiumgerüst der Installation dringt in der Waagerechten, einer Kanüle gleich, in die Wand ein; in der Vertikalen strebt es hinauf zur Decke der Kunsthalle. Als Vorlage der skizzenhaften Konstruktion diente die Fassade jenes Hauses, in dem die Künstlerin große Teile ihrer Kindheit verbracht hat. Die Erinnerung an zurückgelassene Orte ist ein verbindendes Element ihrer Arbeiten. So auch in der Fotografie untitled (48°32’27.0 „N 22°59’40.7 „E), die mit dem von der Künstlerin entwickelten Transferprint-Verfahren auf Seife hergestellt wurde. Einer transparenten Hautschicht gleich birgt das Material die Abbildung des Hauses – ein verblassendes Erinnerungsbild, im Versuch des Festhaltens begriffen. Der Wunsch des Erhaltens oder Konservierens durch Fotografie oder Cyanotypie und gleichzeitig die Einsicht des Verlustes und der Leerstelle markieren eine Dialektik, die sich in der Stabilität und Instabilität der provisorischen Architektur ebenso wiederfindet wie in der Bewertung von Sicherheit und Gefahr, die durch ein hörbares Signal in der Soundarbeit von Olga Holzschuh erfolgt. Seit dem 14. Jahrhundert ertönt vom Turm von St. Lamberti in Münster ein Hornsignal im Zeichen der Sicherheit und des Friedens – geblasen durch eine:n Türmer:in (aktuell durch die Türmerin Martje Thalmann). Jedoch ertönt das Signal nur in die Himmelsrichtungen des Südens, Westens und Nordens, der Osten wird seit jeher ausgelassen. Das fragile Hauskonstrukt von Olga Holzschuh befindet sich im Osten der Installation. Dem gegenüber stehen drei große Skulpturen in Form von Hohlkegeln. Im Raum verteilt markieren sie die drei genannten Himmelsrichtungen: Süd, West und Nord. Über drei Meter hoch erinnern sie an monumentale Sprachrohre, archaisch tönende Instrumente oder auch an große, sich als Versteck anbietende Schilde. Jede halbe Stunde erklingt inmitten der Installation das Hornsignal der Türmerin, das die Bevölkerung ursprünglich über die Sicherheit der Stadt informierte.

From the street through a dark driveway, into a shady courtyard, up a flight of stairs, around the corner, through the door. Shimmering aluminium objects, almost three metres high, block the way. They lean upright against the wall on the left, are rounded, become narrow downwards. Green-blue lengths of fabric float around the sculptures made of thin metal, spilling out onto the wooden floor. Olga Holzschuh’s installation silently absorbs the light that falls diagonally into the courtyard. The aluminium sculptures are reminiscent of oversized body parts: empty shells, insect carapaces, fingernails, arms and rounded shoulders. The fabric is not a display, but itself a vague sculpture, part of a structure. Partly it is held by the sculptures leaning against the wall, at the same time the sculptures stand on it – only on a single point, on their tips. Formerly green, the fabric changes to dark blue in diffused patterns. As a huge cyanotype, it photoreactively reproduces the light situation(s) in the room.

You could call Olga Holzschuh’s installation surreal. However, one should not neglect the reference to reality in her practice: Holzschuh started her work in photography. Today, she still collects indexically—just in different techniques. She collects imprints and traces of poses and postures of the human body. With elbows, necks and shoulders, she particulary focuses on the body‘s supporting structures. In previous works, she has photographed, moulded or repetitively traced her own body parts and those of other people. Her series of cropped joints and bones resemble studies. With the body we move through the world, we perceive the environment and we react to it with it, almost „seismographically“: with tension, flexible looseness, an open posture or curved defensiveness. Holzschuh is less concerned with individual aspects in her studies. She examines the psychological states and mental attitudes that express themselves in different postures. Since 1981, the Moltkerei-Werkstatt¹ has presented unfinished, processual art; for a long time, it stood specifically for performances and installation sculptures rooted in the art of the 1970s. Body, observation and the collective traditionally meet here. Holzschuh’s quasi-phenomenological orders now point to the body in the present: as a physical force field as well as a sign. Her „bent necks“ and „cold shoulders“ point to the signalling function of the body in the social realm and also its significant role in photographs circulating online. Today, more than ever, the body is under constant observation. Especially in times of instability and crisis, it shows itself as a physical crystallisation point of social forces—of standardisation, sexualisation, fetishisation, exploitation or (self-)optimisation.

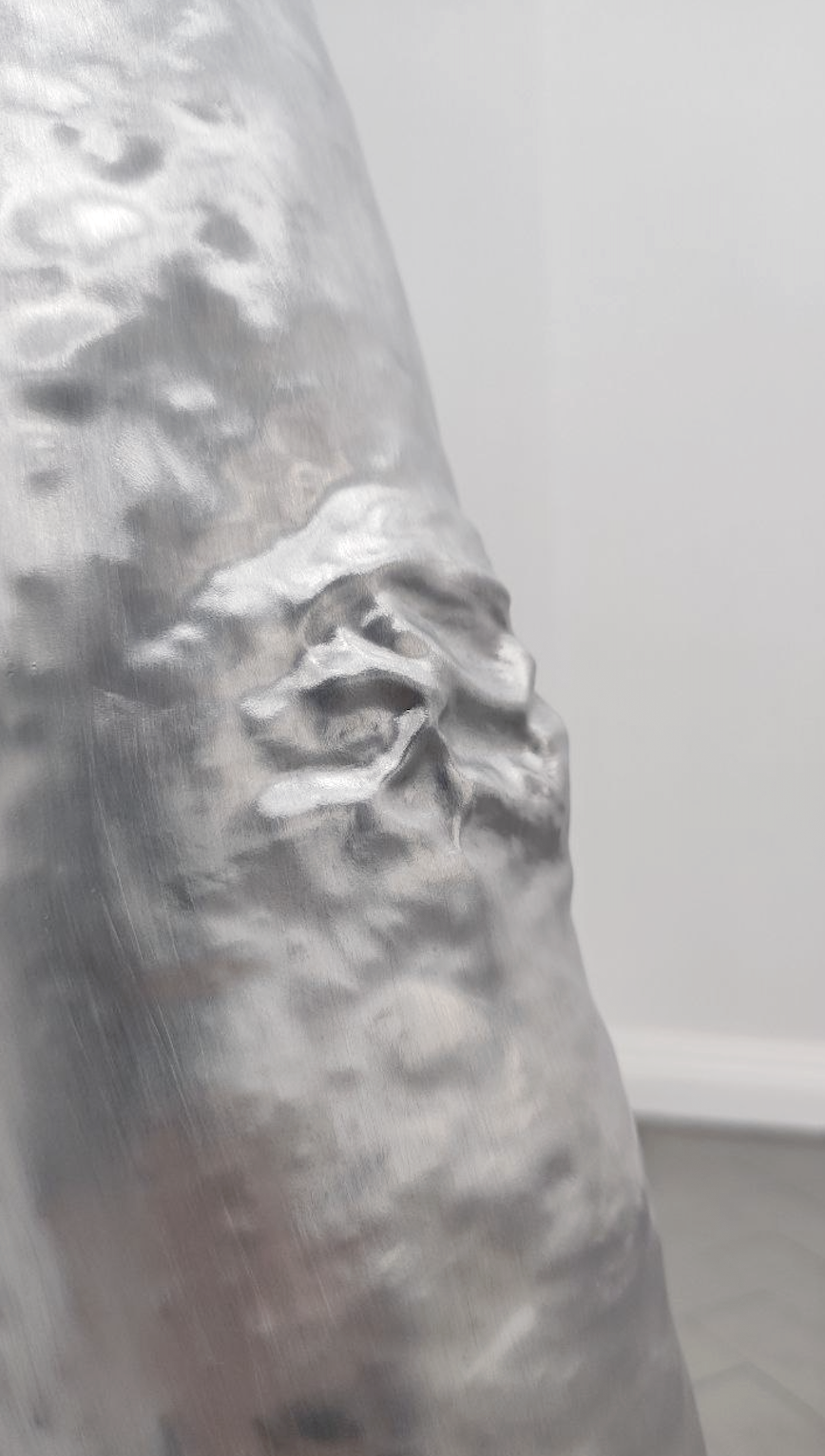

The sculptures, which are much larger than herself, were hewn into shape by Olga Holzschuhs own bodily strength inside out. In this process, she has run up against her own physical limits. She molded her body into the sculptures and thus added a very personal dimension to them. On the other hand, the shoulder in the sculpture’s upper part is abstracted, seems monstrous in its inflated scale and uneven surface structure. Like sea creature shells, the objects hide their interior from the viewer. Due to their downward tapered form, the sculptures simultaneously appear like standing figures—classical sculptures. Like Isa Genzken’s „Hyperbolos“ they are similary related to and at the same time alienated from humans. Since 1982, Genzken no longer placed her „Hyperbolos“ on the floor, but leaned them against the wall, making them turn into „persons“ even more than before.

None of Holzschuh’s figures stands on its own. Together with the rhythmically placed, technically smooth supports and the canvas, the standing sculptures form a fragile static system. If one element falls away, this system collapses. Gravity, which affects all kinds of bodies, becomes visible. For philosopher and activist Simone Weil, life is primarily determined by light and gravity: „Two forces rule the universe: light and gravity.“² According to her aphorisms, life is constant work against gravity; it follows fine mechanics, runs in amplitudes and is in constant change. What structures and forces hold us? What makes them waver? And what situations, co-existences and practices do we hold ourselves to?

In her essay „Formless“, Rosalind Krauss describes the production of monstrous, uncanny images as a protective strategy: „To produce the image of what one fears, in order to protect oneself from what one fears – this is the strategic achievement of anxiety, which arms the subject, in advance, against the onslaught of trauma, the blow that takes one by surprise.“³ In the tableau that Holzschuh’s installation creates, even one more image emerges, as an imprint in the photoreactive fabric. Where light acts, the fabric turns dark blue. The shadows and reflections of the sculptures, the light leave traces in the fabric. Exposed and shadowed parts mix with the actual shadows of the fabric folds. The exhibition time is the exposure time. Waiting for an uncertain image. What happens afterwards is Olga Holzschuh’s decision: she can stop the process, capture the „imprints“ in the fabric by washing out the chemistry with water. Or she can expose the traces created in the installation completely to the light and let them disappear in the dark blue.

Juliane Duft

____________________________________________________________________

1 The Moltkerei-Werkstatt, located in a Cologne backyard, has always remained a workshop. Since 1989, it has been a place for processual art based on physical experience, in the wake of Happening and Fluxus. Artists such as Marina Abramovic and Ulay, Terry Fox and Peter Weibel have exhibited here. „Artists lived and worked in the space on Moltkestraße for a few weeks or days and developed an art in transformation at the site,“ Jürgen Kisters describes the site-specific practice, „(…) thus a jump from the stairs into the depths of the garage in the courtyard of the Moltkerei- Werkstatt demonstrates the concept of an expanded concept of art that places the process (sic!) above the finished work of art.“ S. Jürgen Kisters: Die Kölner Moltkerei-Werkstatt, in: Kunstforum, vol. 117, 1992.

2 Simone Weil: Gravity and Grace (1952), London 2002, p. 1.

3 Rosalind Krauss: Uncanny, in: Yve-Alain Bois, Rosalind Krauss: Formless: A User’s Guide, New York 1997, pp. 192-197, here p. 196.

please scroll down for the german (original) version

hold on, Moltkereiwerkstatt 2022, cotton fabric, cyanotypie, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, installation: 800cm x 330cm

hold on, Moltkereiwerkstatt 2022, cotton fabric, cyanotypie, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, installation: 800cm x 330cm

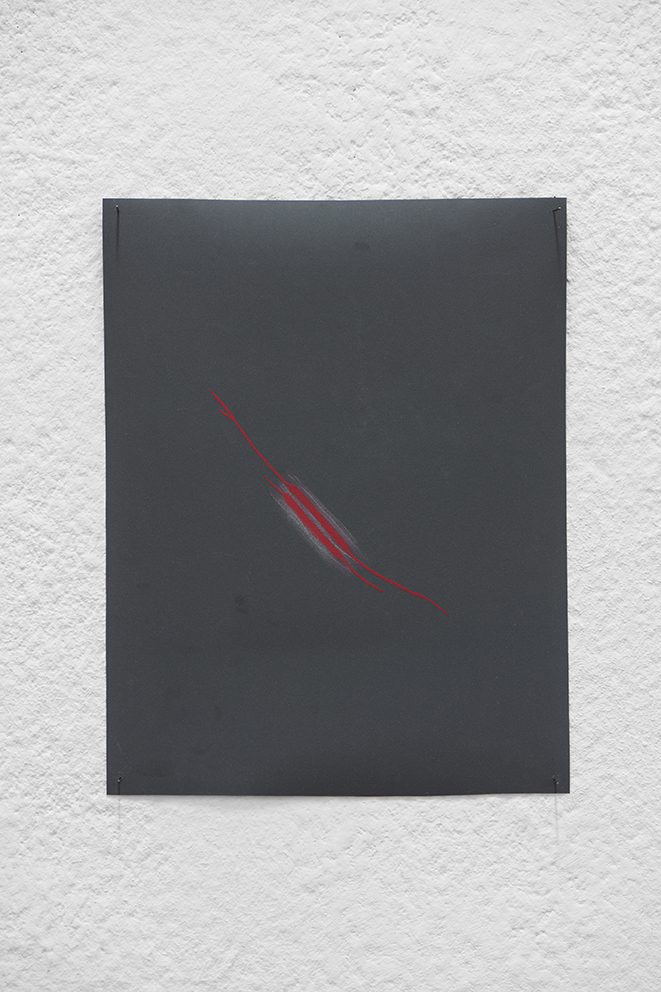

untitled (Tendonitis), Moltkereiwerkstatt, 2022, 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper

untitled (Tendonitis), Moltkereiwerkstatt, 2022, 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper

hold on

Von der Straße durch eine dunkle Einfahrt, in einen schattigen Hof, eine Treppe hoch, um die Ecke, durch die Tür. Fast drei Meter hohe, schimmernde Aluminium-Objekte versperren den Weg. Sie lehnen aufrecht an der Wand links, sind gerundet, laufen schmal nach unten zu. Grün-blaue Stoffbahnen umspülen die Skulpturen aus dünnem Metall, laufen auf dem Holzboden aus. Olga Holzschuhs Installation saugt still das Licht auf, das schräg in den Hof fällt. Die Aluminium-Skulpturen erinnern an übergroße Körperteile: leere Hüllen, Insektenpanzer, Fingernägel, an Arme und an gerundete Schultern. Der Stoff ist nicht Display, sondern selbst vage Skulptur, Teil eines Gefüges. Teilweise wird er von den an die Wand lehnenden Skulpturen gehalten, gleichzeitig stehen diese auf ihm – nur auf einem Punkt, auf ihren Spitzen. Ehemals grün, verändert sich der Stoff in diffusen Mustern zu Dunkelblau. Als riesige Cyanotypie bildet er photoreaktiv die Lichtsituation(en) im Raum ab.

Man könnte Olga Holzschuhs Installation surreal nennen. Man sollte den Realitätsbezug ihrer Praxis jedoch nicht vernachlässigen: Holzschuh begann ihre Arbeit in der Fotografie. Noch heute sammelt sie indexikalisch, nur in unterschiedlichen Techniken. Sie sammelt Abdrücke und Spuren von Posen und Haltungen des menschlichen Körpers. Mit Ellenbogen, Nacken und Schultern fokussiert sie insbesondere seine Halt gebenden Strukturen. In vorherigen Arbeiten hat sie ihre eigenen Körperteile und die von anderen Personen fotografiert, abgeformt oder repetitiv nachgezeichnet. Ihre Serien von ausschnitthaft gezeigten Gelenken und Knochen ähneln Studien. Mit dem Körper bewegen wir uns durch die Welt, nehmen wir die Umwelt wahr und wir reagieren mit ihm auf sie, fast „seismografisch“ mit Verspannungen, flexibler Gelöstheit, einer offenen Haltung oder gekrümmter Abwehr. Holzschuh geht es in ihren Studien weniger um individuelle Aspekte. Sie untersucht die psychischen Zustände und mentalen Haltungen, die sich in verschiedenen Körperhaltungen ausdrücken. Seit 1981 wird in der Moltkerei-Werkstatt ¹ unabgeschlossene, prozesshafte Kunst präsentiert, lange Zeit stand sie speziell für in der Kunst der 1970er Jahre verwurzelte Performances und installative Skulpturen. Körper, Beobachtung und das Kollektive treffen sich hier traditionell. Holzschuhs quasi-phänomenologischen Ordnungen deuten nun auf den Körper in der Gegenwart: als physisches Kraftfeld genauso wie als Zeichen. Ihre „gekrümmte Nacken“ und „kalte Schultern“ verweisen auf die signalgebende Funktion des Körpers im Sozialen und auch seine bedeutende Rolle in online zirkulierenden Fotografien. Der Körper ist heute mehr denn je unter ständiger Beobachtung. Gerade in Zeiten der Instabilität und der Krise zeigt er sich als physischer Kristallisationspunkt von gesellschaftlichen Kräften – von Normierung, Sexualisierung, Fetischisierung, Ausbeutung oder (Selbst-) Optimierung.

Die Skulpturen, die viel größer sind als sie selbst, hat Olga Holzschuh mit ihrer eigenen Körperkraft von innen heraus in Form gehauen. Dabei kam sie Kontakt mit ihren eigenen körperlichen Grenzen. Sie hat ihren Körper in den Skulpturen abgedrückt und ihnen damit doch eine sehr persönliche Dimension hinzugefügt. Die Schulter in ihrem oberen Teil ist dagegen abstrahiert, wirkt in ihrem aufgeblasenen Maßstab und der unebenen Oberflächenstruktur monströs. Wie Meerestier-Schalen verbergen die Objekte ihr Inneres von den Betrachter*innen. Durch ihre sich nach unten hin verjüngende Form wirken die Skulpturen gleichzeitig wie stehende Figuren – klassische Skulpturen. Sie verhalten sich ähnlich nah wie gleichzeitig entfremdet zum Menschen wie Isa Genzkens „Hyperbolos“. Seit 1982 legte Genzken sie nicht mehr auf den Boden, sondern lehnte sie an die Wand und ließ sie so noch mehr als zuvor zu Personen werden.

Keine von Holzschuhs Figuren steht für sich. Zusammen mit den rhythmisch gesetzten, technisch-glatten Stützen und dem Canvas bilden die stehenden Skulpturen ein fragiles statisches System. Fällt ein Element weg, bricht dieses System in sich zusammen. Die Schwerkraft, die an allen Arten von Körpern zehrt, wird sichtbar. Für die Philosophin und Aktivistin Simone Weil ist das Leben primär von Licht und Schwerkraft bestimmt: „Two forces rule the universe: light and gravity.“ ² Leben ist gemäß ihrer Aphorismen stetiges gegen die Schwerkraft an-arbeiten; es folgt feinen Mechaniken, verläuft in Amplituden und befindet sich in stetiger Veränderung. Welche Strukturen und Kräfte halten uns? Was bringt sie zum wanken? Und an welchen Situationen, Ko-Existenzen und Praktiken halten wir uns selbst fest?

In ihrem Werk „Formless“ beschreibt Rosalind Krauss das Herstellen von monströsen, unheimlichen Bildern als Schutz-Strategie: „To produce the image of what one fears, in order to protect oneself from what one fears – this is the strategic achievement of anxiety, which arms the subject, in advance, against the onslaught of trauma, the blow that takes one by surprise.“³ In dem Tableau, was Holzschuhs Installation kreiert, entsteht noch ein weiteres Bild, als Abdruck in dem photoreaktiven Stoff. Wo Licht einwirkt, wird der Stoff Dunkelblau. Die Schatten und Reflexionen der Skulpturen, das Licht hinterlassen Spuren im Stoff. Belichtete und verschattete Partien vermischen sich mit den tatsächlichen Schatten der Stofffaltungen. Die Ausstellungsdauer ist die Belichtungszeit. Warten auf ein unsicheres Bild. Was danach passiert ist Olga Holzschuhs Entscheidung: Sie kann den Vorgang anhalten, die „Abdrücke“ im Stoff festhalten, indem sie die Chemie mit Wasser auswäscht. Oder sie kann die in der Installation entstandenen Spuren ganz dem Licht aussetzen – diese im Dunkelblau verschwinden lassen.

Juliane Duft

____________________________________________________________________

1 Die in einem Kölner Hinterhof gelegene Moltkerei-Werkstatt ist immer Werkstatt geblieben. Seit 1989 ist sie Ort für prozessuale Kunst ausgehend vom körperlicher Erfahrung, in Nachfolge von Happening und Fluxus. Künstler*innen wie Marina Abramovic und Ulay, Terry Fox und Peter Weibel haben hier ausgestellt. „Künstler lebten und arbeiteten einige Wochen oder Tage in dem Raum an der Moltkestraße und entwickelten am Ort eine Kunst in Verwandlung,“ beschreibt Jürgen Kisters die ortspezifische Praxis, „(…) so demonstriert ein Sprung von der Treppe in die Garagentiefe im Hof der Moltkerei-Werkstatt das Konzept eines erweiterten Kunst begriffs, der den Prozeß (sic!) über das fertige Kunstwerk stellt.“ S. Jürgen Kisters: Die Kölner Moltkerei-Werkstatt, in: Kunstforum, Bd. 117, 1992.

2 Simone Weil: Gravity and Grace (1952), London 2002, S. 1.

3 Rosalind Krauss: Uncanny, in: Yve-Alain Bois, Rosalind Krauss: Formless: A User’s Guide, New York 1997, S. 192–197, hier S. 196.

curated by Juliane Duft

Photo Credits Mareike Tocha

Graphic Design Timo Wissemborski

the head is pulled forward and tilted into the neck

the upper back is severely rounded, in extreme cases a hunchback

the shoulders are pulled up and forward

the chest is sunken inwards and fixed in the exhalation position

the arms are rotated inwards, such that the backs of the hands face forwards

the arms do not hang next to, but in front of the body

the hip joints are bowed

the feet often no longer roll over

the gait is small-stepped

the torso is stiff when walking

The tension pattern “Red Light Reflex” can appear as an acute reflex or as a chronic, permanent contraction and corresponds with the body image of a fear and protection response. It may be triggered by constant stress, sensory overload, traumas, or habitual bad posture. A bent-over sitting position while doing desk work contributes to developing the condition.

Olga Holzschuh’s exhibition at Philipp Pflug Contemporary is titled after said phenomenon, and presents three groups of works, including sculptures, photographs, and drawings, together for the first time. Made by hand from aluminum according to the artist’s cubit (an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger of an average man), elbows stand in a precarious balance in the exhibition space, while Vaseline-covered forms of shoulders lean against the wall, supported by thin aluminum rods. A step in the wrong direction, a careless moment, and they could fall. And further: sculptures made of bent steel echoing the yoga pose of the upward facing dog, photo transfer prints on soap of twisted ankles, a pink wall. It is the hue “Cool-Down-Pink-One” which is increasingly used (and popular) in prisons and psychiatric wards. Color psychology attributes a calming and even aggression-inhibitive effect to the shade – there is, however, no scientific proof for this effect.

Holzschuh develops her cross-media works out of her investigation into the impact of environment and stress on body and mind, into the strategies a society geared towards productivity has concocted to counteract the permanent state of crisis – always on the verge of collapse. An excess of stimuli, information and impulses not only affects the individual body, but also radically changes the economy of attention. In The Burnout Society Byung-Chul Han describes multitasking as a reactionary technique that is essential to survival in the wilderness in the animal kingdom, yet not beneficial as a cultural behavior in humans, as a deep, contemplative structure thus gives way to a broad dispersion.

In a precisely choreographed and delicate balancing act, Holzschuh creates focused moments of fragility and instability in which – led by the demand for optimization and resilience – incessant attempts are made to regain control over bodily and mental states before it slips away.

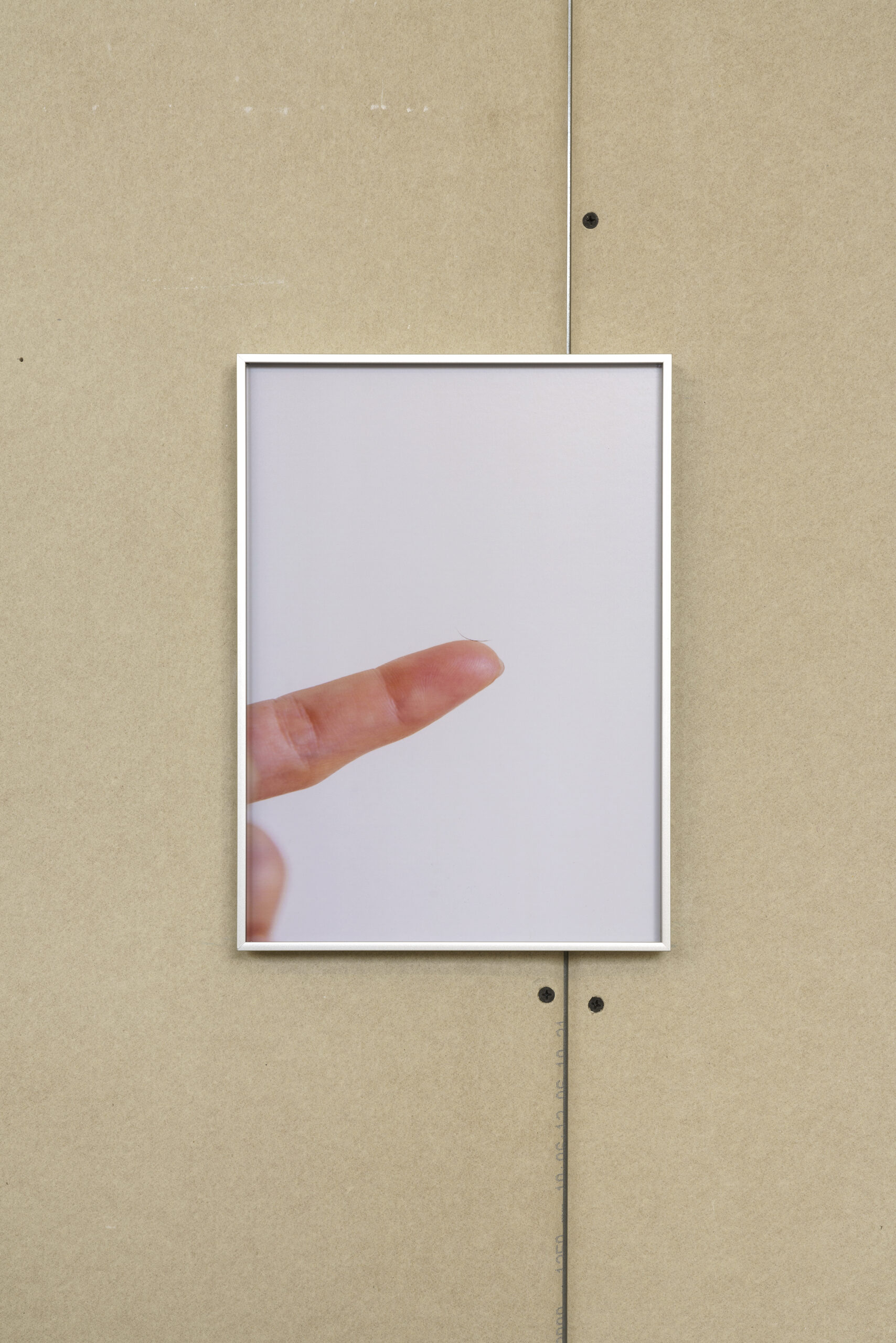

An eyelash balances on a fingertip.

Make a wish.

Text: Miriam Bettin

_____________________________________________________________________

1 Byung-Chul Han (2018). Müdigkeitsgesellschaft. Burnoutgesellschaft. Hoch-Zeit (The Burnout Society). Berlin: Matthes & Seitz. pp. 26 et seq.

RED LIGHT REFLEX 2020-2022 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet,

Vaseline, variable size

max. 254 x 55 x 160 cm

RED LIGHT REFLEX 2020-2022 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet,

Vaseline, variable size

max. 254 x 55 x 160 cm

UNTITLED (EYELASH) 2021

/ Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

C-Print, framed

29,5 x 21,5 cm

UNTITLED (EYELASH) 2021

/ Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

C-Print, framed

29,5 x 21,5 cm

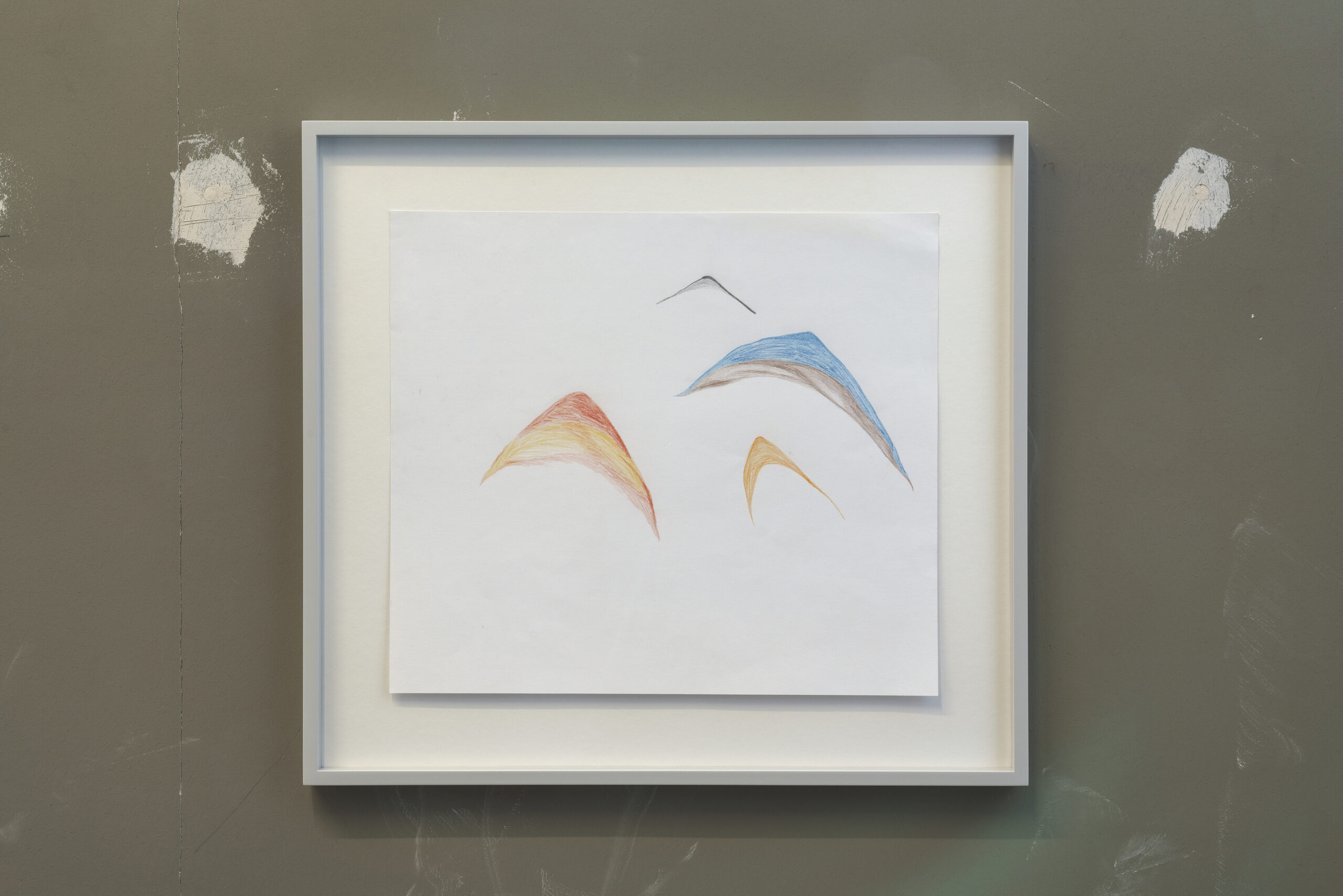

UNTITLED (STUDIES ON THE ELBOW) 2021

/ Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

54 x 59 cm

UNTITLED (STUDIES ON THE ELBOW) 2021

/ Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

54 x 59 cm

DISBALANCE, 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

glycerine soap, transfer print, plexiglas

38 x 31 x 6 cm

DISBALANCE, 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

glycerine soap, transfer print, plexiglas

38 x 31 x 6 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE I) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

charcoal pencil on sandpaper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE I) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

charcoal pencil on sandpaper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

40 x 120 x 13 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

40 x 120 x 13 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE II) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE II) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE III) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE III) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE IV) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE IV) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE V) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

UNTITLED (FRACTURE V) 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

coloured pencil on paper, framed

38 x 28,5 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

202 x 9 x 10 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

202 x 9 x 10 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

82 x 120 x 11 cm

RESILIENCE FORTY-THREE POINT TWO 2021 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

handmade aluminium sheet

82 x 120 x 11 cm

COBRA IN TRANSITION 2019 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

two steel tubes, bent,

76 x 200 x 50 cm

+

2 x UNTITELD (NECK 2-3), 2019

C-Print, Plexiglas

25,5 x 21 cm

COBRA IN TRANSITION 2019 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

two steel tubes, bent,

76 x 200 x 50 cm

+

2 x UNTITELD (NECK 2-3), 2019

C-Print, Plexiglas

25,5 x 21 cm

PLANK 2019 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

two steel tubes, bent,

48 x 200 x 20cm

+

1 x UNTITELD (NECK 1), 2019

C-Print, Plexiglas

25,5 x 21 cm

PLANK 2019 / Philipp Pflug Contemporary,

two steel tubes, bent,

48 x 200 x 20cm

+

1 x UNTITELD (NECK 1), 2019

C-Print, Plexiglas

25,5 x 21 cm

Photo Credit: Wolfgang Günzel

Simone Weil, in her notebooks that would later be published as Gravity and Grace, describes the inescapable force that drags us

all down as a condition of our creation. Ever since the maker’s cord was cut at the knot of our navels we’ve been plummeting. A hidden force that spares no one and no thing, from funus to funis,¹ this is the way we fall.

Can we be relieved of this burden? The graceful practice of Decreation, Weil replies, will ‘make things come down without weight.’² We must unmake ourselves and our hall of mirrors. Beyond the security of the frame and within the slackening loops, pleats, blemishes and puckers, disorientation is an opportunity for new cartographies and minglings.

(…) To fathom [from the German Faden] the world, we embrace it with outstretched arms. We have always measured in spans of hands, feet and forearms, instrumenting our frailties to make the material world robust, containable, to make space yield. In addition to jost-ling away undesirables, or propping up one’s boredom, the Ancient Egyptians used the elbow as a vital measure: the cubit – the length of a man’s arm from his elbow to middle fingertip. The Great Pyramid of Giza was 280 cubits high. We have not ceased to extend our soft rulers and with a clenched fist hammer everything into shape. Upon a fall, the elbow fractures easily. (…)

(excerpt from a longer text by)

Ella Lewis-Williams

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

¹ Francis Ponge, ‘The New Spider’ in Things, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971, p.108.

² Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, London: Routledge, 2002, p.4.

³ The root of the word ‘text’ is literally „thing woven,“ from texere „to weave or braid.“

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / handmade aluminium sheet, 129,6cm x 10cm, 3-pcs., 6-pcs. / untitled (fracture II), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed

resilience forty-three point two / handmade aluminium sheet, 129,6cm x 10cm, 3-pcs., 6-pcs. / untitled (fracture II), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed

left: untitled (fracture II) right: untitled (fracture III), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed / 6-pcs

left: untitled (fracture II) right: untitled (fracture III), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed / 6-pcs

untitled (fracture I), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper, framed

untitled (fracture I), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper, framed

installation view, 2020 ©liebschuh

installation view, 2020 ©liebschuh

Disbalance, 2020, glycerine soap, transfer print, 26 cm x 35cm ©liebschuh

Disbalance, 2020, glycerine soap, transfer print, 26 cm x 35cm ©liebschuh

que se ra, 2020, lead cast (in water glass + water), 12 - pcs., variable size ©liebschuh

que se ra, 2020, lead cast (in water glass + water), 12 - pcs., variable size ©liebschuh

untitled (eyelash), Eyelash, Sellotape, 2020, variable size ©liebschuh

untitled (eyelash), Eyelash, Sellotape, 2020, variable size ©liebschuh

untitled (eyelash), Eyelash, Sellotape, 2020, variable size ©liebschuh

untitled (eyelash), Eyelash, Sellotape, 2020, variable size ©liebschuh

red light reflex, 2020, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, Vaseline, 5-pcs., variable size ©liebschuh

red light reflex, 2020, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, Vaseline, 5-pcs., variable size ©liebschuh

Untitled, 2020, Edition 21, Risoprint, 28 cm x 40 cm / Seite 1 ©liebschuh

Untitled, 2020, Edition 21, Risoprint, 28 cm x 40 cm / Seite 1 ©liebschuh

Untitled, 2020, Edition 21, Risoprint, 28 cm x 40 cm / Seite 2 ©liebschuh

Untitled, 2020, Edition 21, Risoprint, 28 cm x 40 cm / Seite 2 ©liebschuh

Things are insecure, but solid

Warten auf die Bombe. „How should we respond to the entwined trajectories of seemingly inevitable technological progress and a planet careening toward ecological collapse?

We resist. And we focus on the arts of living.”

Wir halten unsere eigenen Meditationen unter Bäumen, Bänken und auf Betonböden ab – über Wasser, Wein und manchmal über der Nr. 13 von Ni Hao. „Earthly survival.“ Warten auf die Bombe, oder auf viele kleine Bomben. Dabei Schultern zurück, Brust raus. Die Schilde sind fragil, man muss sie selbst halten. Ohne sie fallen Körper in Körper. Quallen, tentakelnd treibend, sind das neue Rhizom, die neuen Pilze, sagte neulich jemand. Transparent schimmern sie, manche bioluminescent. Weich, aber wirksam, mit Waffen ausgestattet: Verbrennungen auch im Wasser; dichter Gallert, in dem Flugzeugträger feststecken. Quallen haben einen komplexen Lebenszyklus: Die Medusa ist die sexuelle Phase, die Planula-Larve kann sich weit zerstreuen und es folgt eine sitzende Polypenphase. Ihr Leben ist eng verwoben mit den Koexistenten ihres Schwarms und anderen Spezies. Die enge Koexistenz ist nicht leicht – Corona-Lektionen. Aber sie ist das Einzige: Nicht den Progress, nicht den Individualismus, keine Autonomie suchen – nicht Moby Dick, Flipper, Weißer Hai oder Free Willy sein. Kein „shoulder rubbing“. Stattdessen Symbiosen eingehen, Intensitäten zulassen. Sich weich machen, sich verstricken. „Multispecies monsters“ : Hinwendung, im Meer aufgehen, Zukunft ohne Wirbel.

„Woman, living in the moment’ finds unfortunately it is connected to other moments,“ lese ich vor. Auch Momente sind tentakelnde Quallen, neuronale Extravaganzen. Insbesondere im Leben deutscher Großstädter im Jahr 2020 sind die Dinge weich und klebrig. Dazu noch ein Zitat von Tom McCarthy: „Das Reale einer Sache liegt in ihrer eigenen Materialität: einer klebrigen, unstrukturierten und vor allem niederen Materialität, die alle Grenzen überschwemmt oder unterspült, welche die Identität einer Sache eindämmen oder abstecken.“ Die Materie, die physischen Körper sind bestimmend – eine schöne wie unheimliche Vorstellung. Sie steht auf, dehnt sich und schaut mich über ihre Schulter an. Ich mache ein Foto und poste es in meine Story.

Juliane Duft

__________________

1 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al., Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts And Monsters of the Anthropocene, 2019.

2 S. Donna Haraway, Unruhig bleiben, 2018 und Tom McCarthy, Schreibmaschinen, Bomben, Quallen, 2019 sowie den Artikel von Rudi Nuss, „Wasser zu Wasser (Or: The Life Without Bones)“, in: Die Epilog, Ausgabe Nr. 8, 2019.

3 Tsing, 2019.

4 Meme, um 2016.

5 McCarthy, 2019.

We are intervening in the last area that we cannot control, our safe zone and last resort for healing processes: sleep. Near-body-technologies are our unsolicited accomplices by measuring our bodies at night for an efficient performance during everyday life. When we finally let go and leave ourselves to sleep these technologies stay awake. How tired must our devices be recording, measuring, observing every tiny movement we make at night while being our intimate partners collaborating to maintain self-control even during sleep.

The Video Installation ~ 490 nm away from you expresses a desire to regard sleep as a form of refusal against its late capitalist economization. The work speculates on strategies of collaboration to break with the logics of optimization by putting both, humans and machines, finally to sleep.

For full length version please contact info@olgaholzschuh.com

Atem. is a performative ’setting‘ that sees the breath as an essential, everyday ritual, both individual and collective. How is the physical and psychological shortage of air while breathing related to individual, as well as social and geopolitical crises? And how is breathing also subject to the benefits of a hypercapitalized culture?

Inhale, Performance-Breath, filled at 17/1/20 for 2,50Euro

Inhale, Performance-Breath, filled at 17/1/20 for 2,50Euro

In her 2018 book Carceral Capitalism Jackie Wang describes contemporary solitary confinement models and incarceration procedures that have been practiced since the 1990s, primarily in the USA. She addresses youth criminality, corrupt policing and economic systems based on fines and debt, tracing power structures and cogently critiquing the racist capitalism of our governments. Olga Holzschuh (born in 1985 in Hungary, lives and works in Cologne) adopts aspects and symbols of the hierarchical structures Wang implicates, bringing them together at KOENIG2 in the expansive installation I wish you were different – her first solo exhibition in Austria. Semiotically, the work makes visible mechanisms of public and private space, opening a discourse on systemic regulation and on the affects and rituals that oppose it.

The entire exhibition space is bathed in an intense pink, a color selected psychologically for its calming or even sedating effects. Special prison cells are painted in this hue for the purpose of calming and emotionally stabilizing particularly aggressive or violent inmates. The color is patented in Switzerland under the name Cool Down Pink, although its actual effectiveness has never been scientifically proven. The origins of this trend in affective control lie in the 1960s and 70s. Alexander Schauss investigated this phenomenon, developing the so-called Baker-Miller Pink, named after the prison directors of the Naval Correctional Institute in Seattle, which served as the color’s first testing ground. In the meantime, variations of the color have come into use in painting psychiatric wards, high-security cells and shelters.

Sensuously, the color condenses into the essence of a complex emotional control strategy. In today’s society, such strategies are also implemented in the private sphere for self-preservation and as a means of self-optimization. Simultaneously, vulnerability and stress, but also strength, are insinuated through the photographic depiction of a special, bared stretch of skin that arises through the nodding of the head: the nape of the neck. In Holzschuh’s minimal photos, this area of the body reveals itself in a presence at once uncanny and seductive, as an interface between body and mind, and as a symbol of the power and powerless that can be manifested in it. The human body is foregrounded in Holzschuh’s investigation – as the point where authoritarian control, resilience, activity and fragility converge.

Taking as her point of departure the alterations that arise in thought, action and feeling under the influence of control mechanisms, Olga Holzschuh develops semiotic systems for thinking about the present and the future. Such manifestations are also on the rise in the digital realm. In photography and in videos, objects and installations, attention is focused on gestures and poses that oscillate between seemingly irreconcilable opposites: power and powerlessness, activity and passivity, self-defense and defenselessness, violence and nonviolence, fragility and stability. I wish you were different, the show’s title, shimmers between rebuke, threat and – perhaps – a utopian melancholy wish. It carries a dark premonition of personal destabilization, but at the same time the idealism of a sentimental plea. And it poses the essential question of whether someone or something is in a position to embark on change.

(Andrea Kopranovic, 2019)Olga Holzschuh | I wish you were different

07. 03. – 20. 04. 2019 / Koenig2 Gallery / Vienna (Austria)

The exhibition is presented within the framework of the festival FOTO WIEN (20 March – 20 April 2019) under the title Bodyfiction.