SAKURA (Residency at Goethe Institut Kyoto, Villa Kamogawa)

„The sakura, a tree of great cultural and economic importance in Japan, is also a seismograph for ongoing climate change. According to researchers such as Aono Yasuyuki and various sakura-mori (tree doctors), in the future it will not only bloom earlier than it does today, it will not bloom at all due to the lack of cold winters. In order to approach the sakura* on several levels – its history, its (tourist-friendly) infrastructure, its cultural production, its losses and gaps due to climate change – Olga Holzschuh first travelled around the country and documented the oldest sakura trees in Japan and some in the world, some of them without their blooming blossoms – as „skeletons of the future“. (…)“ source: @goetheinstitut_villakamogawa

This footage was shot as part of my research for the Artist in Residency programme at the Villa Kamogawa, Goethe Institute in Kyoto (mid Jan – mid April 2025). It forms the basis of something that is still in the process, but also something that is very present and already there.

It is combined with excerpts from a performative reading at Villa Kamogawa / Goethe-Institut Kyoto in April 9th, 2025.

The video-footage shows the following sakura trees:

Kanhi Zakura / Okinawa (Detail) is the possible future replacement (necessary due to climate impacts) of (cloned by man) Somei-Yoshino Sakura, the most widely planted tree in Japan and abroad

Kanhi Zakura / Okinawa (in color and shape very different to Somei-Yoshino Sakura)

Miharu Takizakura (Prefecture Fukushima), over 1000 years old

Yamataka Jindai Zakura (Prefecture Yamamashi), 1800-2000 years old

Ishitokaba Zakura, (Prefecture Kitamoto), around 800 years old

Neodani Usuzumi Sakura, (Prefecture Gifu), 1500 year old

The cherry trees in Yoshino have been revered and cultivated as sacred trees for about 1300 years. There are said to be 30,000 of these trees today, most of which are Shiroyamazakura.

Here you can see some impressions from my presentation at the end of my three-month residency at the Goethe-Institut in Kyoto, Japan, on 9 April 2025.

@goetheinstitut_villakamogawa

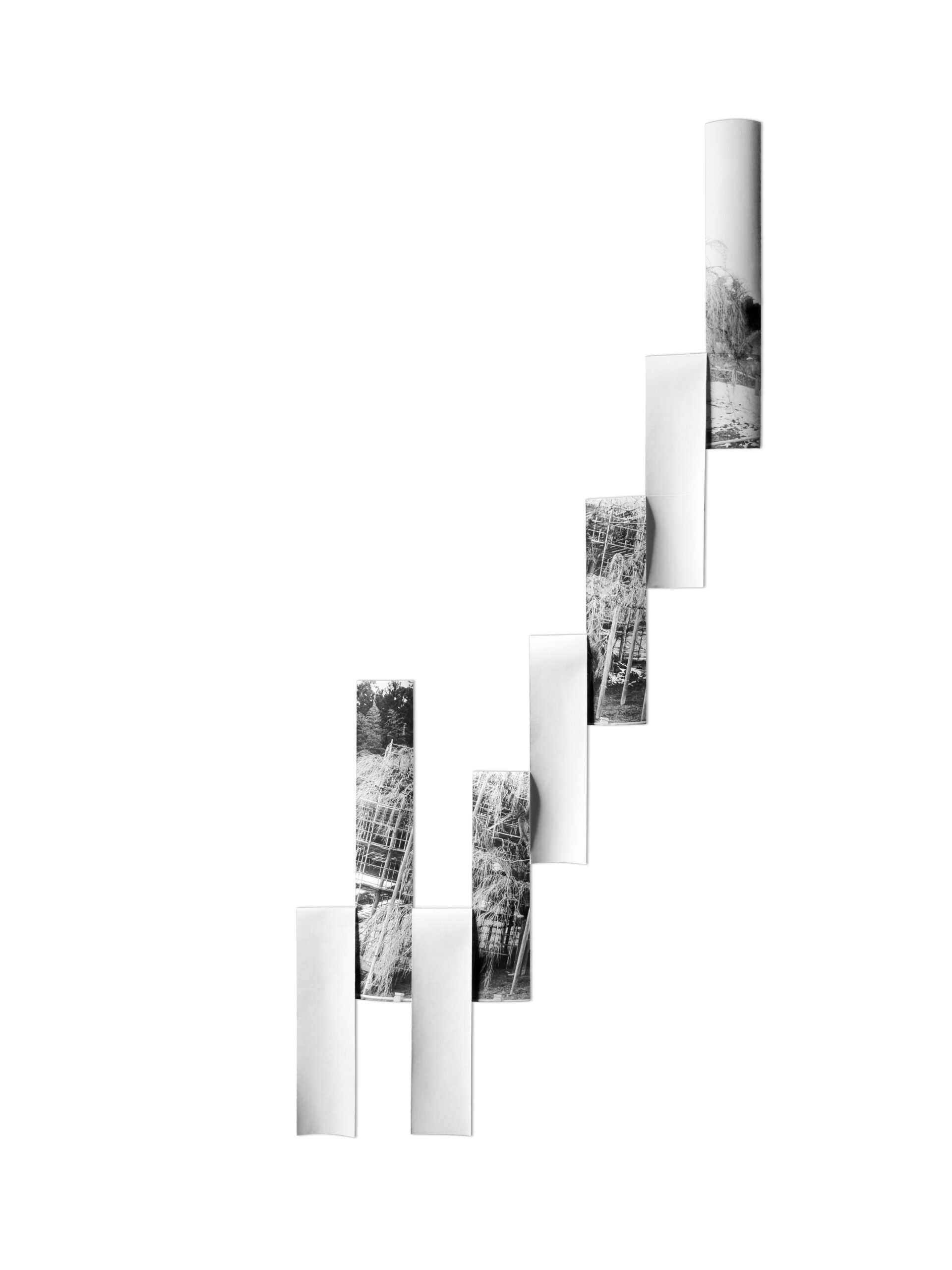

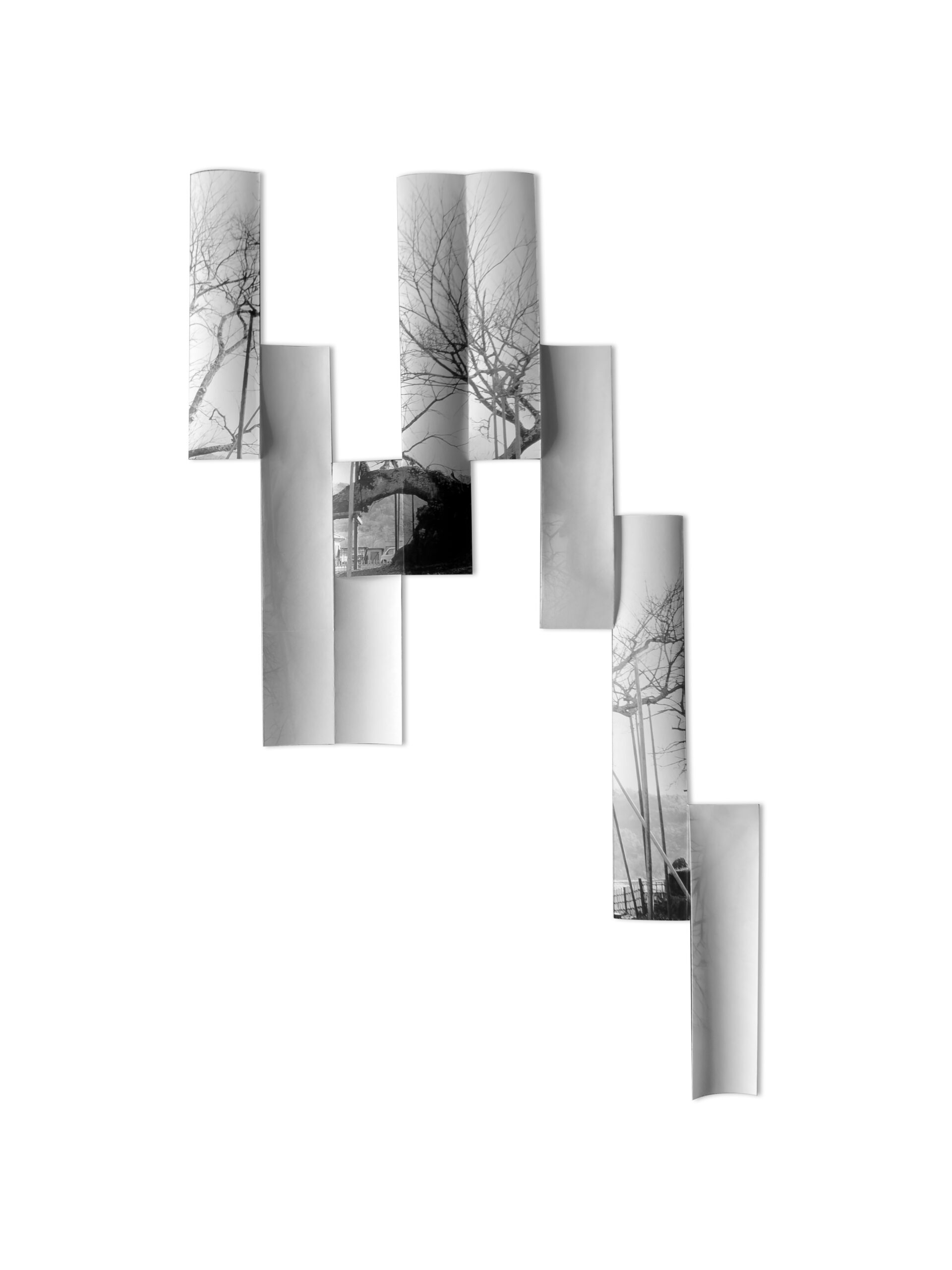

1/3: Miharu Zakura & Yamataka Jondai Zakura, inkjetprint on washi paper, mixed shide-folding/cutout

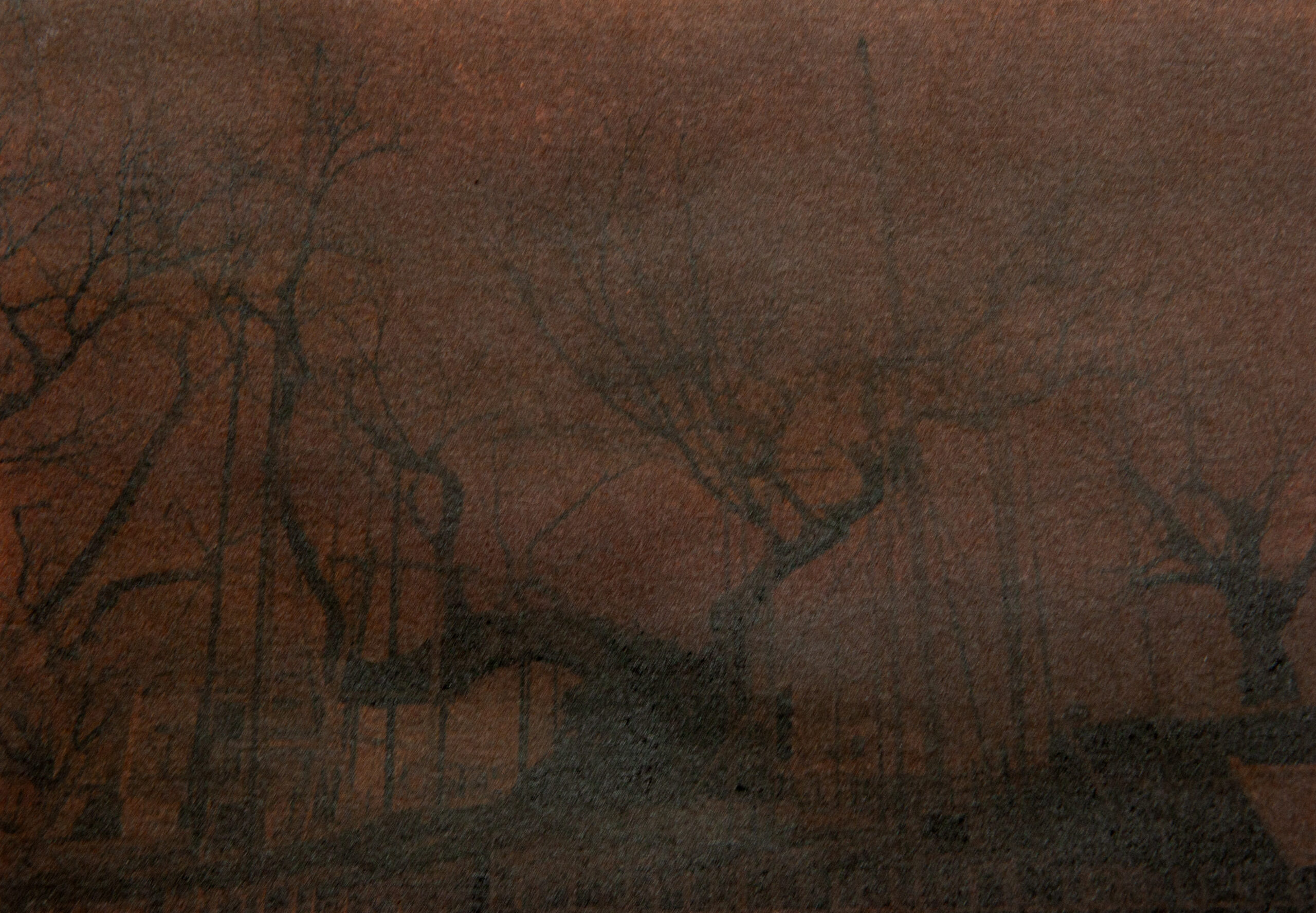

2: Miharu Zakura, inkjetprint on washi paper, urushi lacquer (polish)

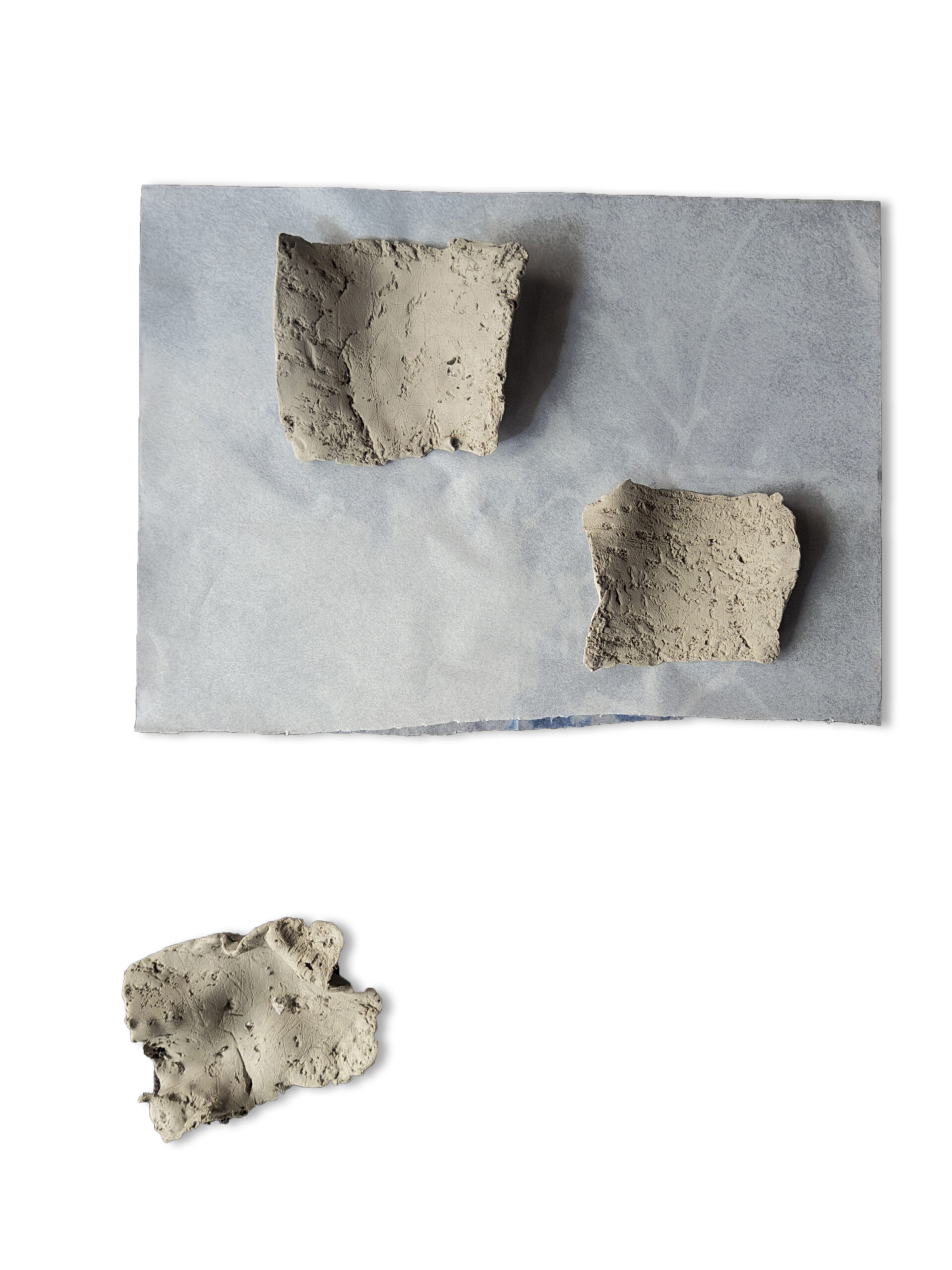

4: imprints of Somei Yoshino bark on Raku Clay, unfired (underneath: transparent washi paper, cyanotype)

5-7: Miharu Takizakura, Yamataka Jindai Zakura, Ishitokaba Zakura, inkjetprint on Washi Paper, Urushi lacquer (basic)

8: presentation view at the „concert hall“ @goetheinstitut_villakamogawa

A little homage to the art of Urushi*, which I had the opportunity to explore in Japan (during my residency @goetheinstitut_villakamogawa earlier this year) – and which I wish to continue working with.

Thanks to Jingyun Shi and her studio @mnystudio_urushi, who introduced me to the essence of this craft with great patience and a spirit open to experimentation – using a material rather unusual for Urushi: photographs printed on high-quality Washi paper. (-> printed by the super professional team of Fine Art Digital Printing; AFLO Tokyo).

The images depict some of the oldest cherry trees in Japan – some even among the oldest in the world. Like the widely cultivated Somei-Yoshino cherry trees, they too are increasingly affected by climate change. This leads not only to ecological but also to significant economic shifts.

I photographed these trees (Miharu Takizakura, Yamataka Jindai Zakura, Ishitokaba Zakura, Neodani Usuzumi Sakura) without their iconic blossoms, and “sealed” them using the Urushi lacquer technique. Here too, time became a crucial element.

Each individual layer of lacquer required precisely defined humidity conditions and took days to dry. The Washi paper seemed to further slow down this process.

I was drawn to this interweaving of time demanded by the material, and the irreversible loss reflected in the depicted motifs.

*Urushi is a traditional Japanese lacquer, extracted from the sap of the Urushi tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum). For centuries, it has been used to refine and preserve wood, ceramics, and other materials. When cured in a humid environment, it forms a surface of great resilience, depth, and sheen – a surface that demands patience, devotion – and silence.

P.S.: I am happy that two pieces from this series have found good homes with @diego.tonus & @alicja_rogalska