hold on

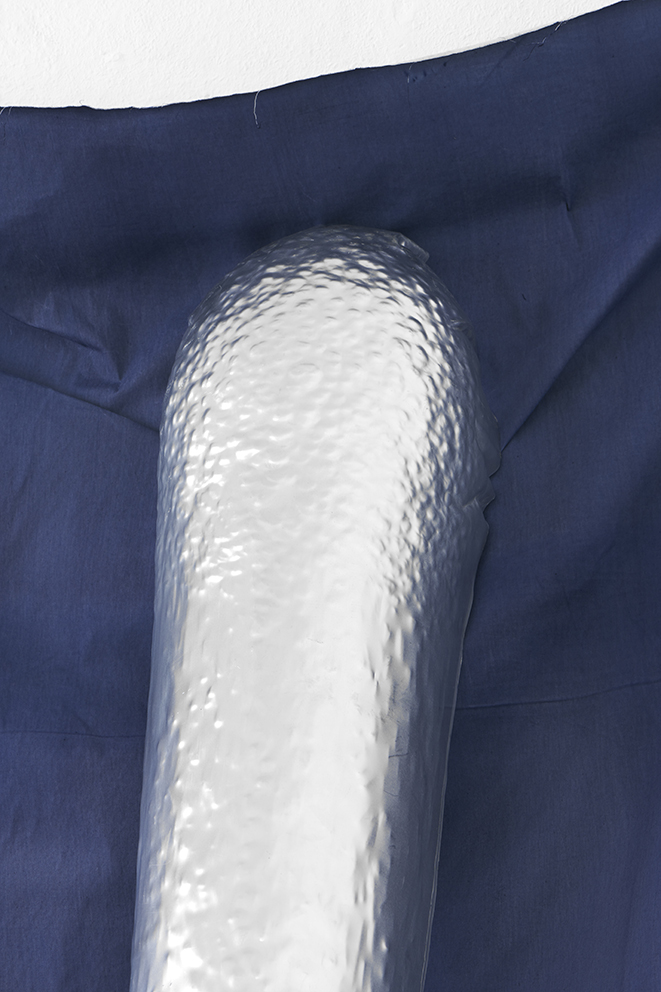

From the street through a dark driveway, into a shady courtyard, up a flight of stairs, around the corner, through the door. Shimmering aluminium objects, almost three metres high, block the way. They lean upright against the wall on the left, are rounded, become narrow downwards. Green-blue lengths of fabric float around the sculptures made of thin metal, spilling out onto the wooden floor. Olga Holzschuh’s installation silently absorbs the light that falls diagonally into the courtyard. The aluminium sculptures are reminiscent of oversized body parts: empty shells, insect carapaces, fingernails, arms and rounded shoulders. The fabric is not a display, but itself a vague sculpture, part of a structure. Partly it is held by the sculptures leaning against the wall, at the same time the sculptures stand on it – only on a single point, on their tips. Formerly green, the fabric changes to dark blue in diffused patterns. As a huge cyanotype, it photoreactively reproduces the light situation(s) in the room.

You could call Olga Holzschuh’s installation surreal. However, one should not neglect the reference to reality in her practice: Holzschuh started her work in photography. Today, she still collects indexically—just in different techniques. She collects imprints and traces of poses and postures of the human body. With elbows, necks and shoulders, she particulary focuses on the body‘s supporting structures. In previous works, she has photographed, moulded or repetitively traced her own body parts and those of other people. Her series of cropped joints and bones resemble studies. With the body we move through the world, we perceive the environment and we react to it with it, almost „seismographically“: with tension, flexible looseness, an open posture or curved defensiveness. Holzschuh is less concerned with individual aspects in her studies. She examines the psychological states and mental attitudes that express themselves in different postures. Since 1981, the Moltkerei-Werkstatt¹ has presented unfinished, processual art; for a long time, it stood specifically for performances and installation sculptures rooted in the art of the 1970s. Body, observation and the collective traditionally meet here. Holzschuh’s quasi-phenomenological orders now point to the body in the present: as a physical force field as well as a sign. Her „bent necks“ and „cold shoulders“ point to the signalling function of the body in the social realm and also its significant role in photographs circulating online. Today, more than ever, the body is under constant observation. Especially in times of instability and crisis, it shows itself as a physical crystallisation point of social forces—of standardisation, sexualisation, fetishisation, exploitation or (self-)optimisation.

The sculptures, which are much larger than herself, were hewn into shape by Olga Holzschuhs own bodily strength inside out. In this process, she has run up against her own physical limits. She molded her body into the sculptures and thus added a very personal dimension to them. On the other hand, the shoulder in the sculpture’s upper part is abstracted, seems monstrous in its inflated scale and uneven surface structure. Like sea creature shells, the objects hide their interior from the viewer. Due to their downward tapered form, the sculptures simultaneously appear like standing figures—classical sculptures. Like Isa Genzken’s „Hyperbolos“ they are similary related to and at the same time alienated from humans. Since 1982, Genzken no longer placed her „Hyperbolos“ on the floor, but leaned them against the wall, making them turn into „persons“ even more than before.

None of Holzschuh’s figures stands on its own. Together with the rhythmically placed, technically smooth supports and the canvas, the standing sculptures form a fragile static system. If one element falls away, this system collapses. Gravity, which affects all kinds of bodies, becomes visible. For philosopher and activist Simone Weil, life is primarily determined by light and gravity: „Two forces rule the universe: light and gravity.“² According to her aphorisms, life is constant work against gravity; it follows fine mechanics, runs in amplitudes and is in constant change. What structures and forces hold us? What makes them waver? And what situations, co-existences and practices do we hold ourselves to?

In her essay „Formless“, Rosalind Krauss describes the production of monstrous, uncanny images as a protective strategy: „To produce the image of what one fears, in order to protect oneself from what one fears – this is the strategic achievement of anxiety, which arms the subject, in advance, against the onslaught of trauma, the blow that takes one by surprise.“³ In the tableau that Holzschuh’s installation creates, even one more image emerges, as an imprint in the photoreactive fabric. Where light acts, the fabric turns dark blue. The shadows and reflections of the sculptures, the light leave traces in the fabric. Exposed and shadowed parts mix with the actual shadows of the fabric folds. The exhibition time is the exposure time. Waiting for an uncertain image. What happens afterwards is Olga Holzschuh’s decision: she can stop the process, capture the „imprints“ in the fabric by washing out the chemistry with water. Or she can expose the traces created in the installation completely to the light and let them disappear in the dark blue.

Juliane Duft

____________________________________________________________________

1 The Moltkerei-Werkstatt, located in a Cologne backyard, has always remained a workshop. Since 1989, it has been a place for processual art based on physical experience, in the wake of Happening and Fluxus. Artists such as Marina Abramovic and Ulay, Terry Fox and Peter Weibel have exhibited here. „Artists lived and worked in the space on Moltkestraße for a few weeks or days and developed an art in transformation at the site,“ Jürgen Kisters describes the site-specific practice, „(…) thus a jump from the stairs into the depths of the garage in the courtyard of the Moltkerei- Werkstatt demonstrates the concept of an expanded concept of art that places the process (sic!) above the finished work of art.“ S. Jürgen Kisters: Die Kölner Moltkerei-Werkstatt, in: Kunstforum, vol. 117, 1992.

2 Simone Weil: Gravity and Grace (1952), London 2002, p. 1.

3 Rosalind Krauss: Uncanny, in: Yve-Alain Bois, Rosalind Krauss: Formless: A User’s Guide, New York 1997, pp. 192-197, here p. 196.

please scroll down for the german (original) version

hold on, Moltkereiwerkstatt 2022, cotton fabric, cyanotypie, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, installation: 800cm x 330cm

hold on, Moltkereiwerkstatt 2022, cotton fabric, cyanotypie, aluminium rod, handmade aluminium sheet, installation: 800cm x 330cm

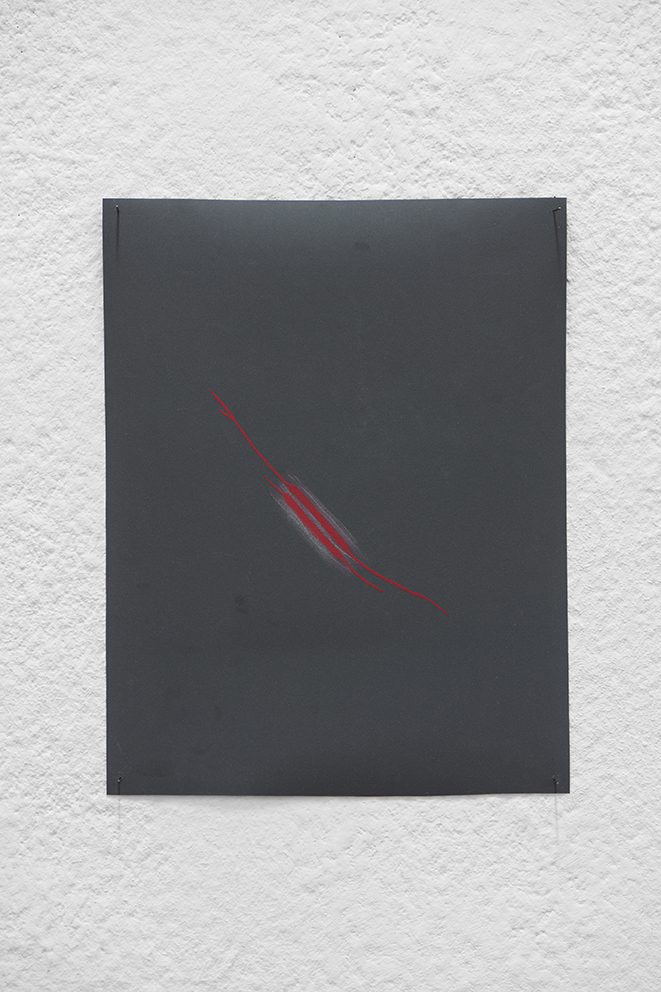

untitled (Tendonitis), Moltkereiwerkstatt, 2022, 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper

untitled (Tendonitis), Moltkereiwerkstatt, 2022, 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper

hold on

Von der Straße durch eine dunkle Einfahrt, in einen schattigen Hof, eine Treppe hoch, um die Ecke, durch die Tür. Fast drei Meter hohe, schimmernde Aluminium-Objekte versperren den Weg. Sie lehnen aufrecht an der Wand links, sind gerundet, laufen schmal nach unten zu. Grün-blaue Stoffbahnen umspülen die Skulpturen aus dünnem Metall, laufen auf dem Holzboden aus. Olga Holzschuhs Installation saugt still das Licht auf, das schräg in den Hof fällt. Die Aluminium-Skulpturen erinnern an übergroße Körperteile: leere Hüllen, Insektenpanzer, Fingernägel, an Arme und an gerundete Schultern. Der Stoff ist nicht Display, sondern selbst vage Skulptur, Teil eines Gefüges. Teilweise wird er von den an die Wand lehnenden Skulpturen gehalten, gleichzeitig stehen diese auf ihm – nur auf einem Punkt, auf ihren Spitzen. Ehemals grün, verändert sich der Stoff in diffusen Mustern zu Dunkelblau. Als riesige Cyanotypie bildet er photoreaktiv die Lichtsituation(en) im Raum ab.

Man könnte Olga Holzschuhs Installation surreal nennen. Man sollte den Realitätsbezug ihrer Praxis jedoch nicht vernachlässigen: Holzschuh begann ihre Arbeit in der Fotografie. Noch heute sammelt sie indexikalisch, nur in unterschiedlichen Techniken. Sie sammelt Abdrücke und Spuren von Posen und Haltungen des menschlichen Körpers. Mit Ellenbogen, Nacken und Schultern fokussiert sie insbesondere seine Halt gebenden Strukturen. In vorherigen Arbeiten hat sie ihre eigenen Körperteile und die von anderen Personen fotografiert, abgeformt oder repetitiv nachgezeichnet. Ihre Serien von ausschnitthaft gezeigten Gelenken und Knochen ähneln Studien. Mit dem Körper bewegen wir uns durch die Welt, nehmen wir die Umwelt wahr und wir reagieren mit ihm auf sie, fast „seismografisch“ mit Verspannungen, flexibler Gelöstheit, einer offenen Haltung oder gekrümmter Abwehr. Holzschuh geht es in ihren Studien weniger um individuelle Aspekte. Sie untersucht die psychischen Zustände und mentalen Haltungen, die sich in verschiedenen Körperhaltungen ausdrücken. Seit 1981 wird in der Moltkerei-Werkstatt ¹ unabgeschlossene, prozesshafte Kunst präsentiert, lange Zeit stand sie speziell für in der Kunst der 1970er Jahre verwurzelte Performances und installative Skulpturen. Körper, Beobachtung und das Kollektive treffen sich hier traditionell. Holzschuhs quasi-phänomenologischen Ordnungen deuten nun auf den Körper in der Gegenwart: als physisches Kraftfeld genauso wie als Zeichen. Ihre „gekrümmte Nacken“ und „kalte Schultern“ verweisen auf die signalgebende Funktion des Körpers im Sozialen und auch seine bedeutende Rolle in online zirkulierenden Fotografien. Der Körper ist heute mehr denn je unter ständiger Beobachtung. Gerade in Zeiten der Instabilität und der Krise zeigt er sich als physischer Kristallisationspunkt von gesellschaftlichen Kräften – von Normierung, Sexualisierung, Fetischisierung, Ausbeutung oder (Selbst-) Optimierung.

Die Skulpturen, die viel größer sind als sie selbst, hat Olga Holzschuh mit ihrer eigenen Körperkraft von innen heraus in Form gehauen. Dabei kam sie Kontakt mit ihren eigenen körperlichen Grenzen. Sie hat ihren Körper in den Skulpturen abgedrückt und ihnen damit doch eine sehr persönliche Dimension hinzugefügt. Die Schulter in ihrem oberen Teil ist dagegen abstrahiert, wirkt in ihrem aufgeblasenen Maßstab und der unebenen Oberflächenstruktur monströs. Wie Meerestier-Schalen verbergen die Objekte ihr Inneres von den Betrachter*innen. Durch ihre sich nach unten hin verjüngende Form wirken die Skulpturen gleichzeitig wie stehende Figuren – klassische Skulpturen. Sie verhalten sich ähnlich nah wie gleichzeitig entfremdet zum Menschen wie Isa Genzkens „Hyperbolos“. Seit 1982 legte Genzken sie nicht mehr auf den Boden, sondern lehnte sie an die Wand und ließ sie so noch mehr als zuvor zu Personen werden.

Keine von Holzschuhs Figuren steht für sich. Zusammen mit den rhythmisch gesetzten, technisch-glatten Stützen und dem Canvas bilden die stehenden Skulpturen ein fragiles statisches System. Fällt ein Element weg, bricht dieses System in sich zusammen. Die Schwerkraft, die an allen Arten von Körpern zehrt, wird sichtbar. Für die Philosophin und Aktivistin Simone Weil ist das Leben primär von Licht und Schwerkraft bestimmt: „Two forces rule the universe: light and gravity.“ ² Leben ist gemäß ihrer Aphorismen stetiges gegen die Schwerkraft an-arbeiten; es folgt feinen Mechaniken, verläuft in Amplituden und befindet sich in stetiger Veränderung. Welche Strukturen und Kräfte halten uns? Was bringt sie zum wanken? Und an welchen Situationen, Ko-Existenzen und Praktiken halten wir uns selbst fest?

In ihrem Werk „Formless“ beschreibt Rosalind Krauss das Herstellen von monströsen, unheimlichen Bildern als Schutz-Strategie: „To produce the image of what one fears, in order to protect oneself from what one fears – this is the strategic achievement of anxiety, which arms the subject, in advance, against the onslaught of trauma, the blow that takes one by surprise.“³ In dem Tableau, was Holzschuhs Installation kreiert, entsteht noch ein weiteres Bild, als Abdruck in dem photoreaktiven Stoff. Wo Licht einwirkt, wird der Stoff Dunkelblau. Die Schatten und Reflexionen der Skulpturen, das Licht hinterlassen Spuren im Stoff. Belichtete und verschattete Partien vermischen sich mit den tatsächlichen Schatten der Stofffaltungen. Die Ausstellungsdauer ist die Belichtungszeit. Warten auf ein unsicheres Bild. Was danach passiert ist Olga Holzschuhs Entscheidung: Sie kann den Vorgang anhalten, die „Abdrücke“ im Stoff festhalten, indem sie die Chemie mit Wasser auswäscht. Oder sie kann die in der Installation entstandenen Spuren ganz dem Licht aussetzen – diese im Dunkelblau verschwinden lassen.

Juliane Duft

____________________________________________________________________

1 Die in einem Kölner Hinterhof gelegene Moltkerei-Werkstatt ist immer Werkstatt geblieben. Seit 1989 ist sie Ort für prozessuale Kunst ausgehend vom körperlicher Erfahrung, in Nachfolge von Happening und Fluxus. Künstler*innen wie Marina Abramovic und Ulay, Terry Fox und Peter Weibel haben hier ausgestellt. „Künstler lebten und arbeiteten einige Wochen oder Tage in dem Raum an der Moltkestraße und entwickelten am Ort eine Kunst in Verwandlung,“ beschreibt Jürgen Kisters die ortspezifische Praxis, „(…) so demonstriert ein Sprung von der Treppe in die Garagentiefe im Hof der Moltkerei-Werkstatt das Konzept eines erweiterten Kunst begriffs, der den Prozeß (sic!) über das fertige Kunstwerk stellt.“ S. Jürgen Kisters: Die Kölner Moltkerei-Werkstatt, in: Kunstforum, Bd. 117, 1992.

2 Simone Weil: Gravity and Grace (1952), London 2002, S. 1.

3 Rosalind Krauss: Uncanny, in: Yve-Alain Bois, Rosalind Krauss: Formless: A User’s Guide, New York 1997, S. 192–197, hier S. 196.

curated by Juliane Duft

Photo Credits Mareike Tocha

Graphic Design Timo Wissemborski