the way we fall

Simone Weil, in her notebooks that would later be published as Gravity and Grace, describes the inescapable force that drags us

all down as a condition of our creation. Ever since the maker’s cord was cut at the knot of our navels we’ve been plummeting. A hidden force that spares no one and no thing, from funus to funis,¹ this is the way we fall.

Can we be relieved of this burden? The graceful practice of Decreation, Weil replies, will ‘make things come down without weight.’² We must unmake ourselves and our hall of mirrors. Beyond the security of the frame and within the slackening loops, pleats, blemishes and puckers, disorientation is an opportunity for new cartographies and minglings.

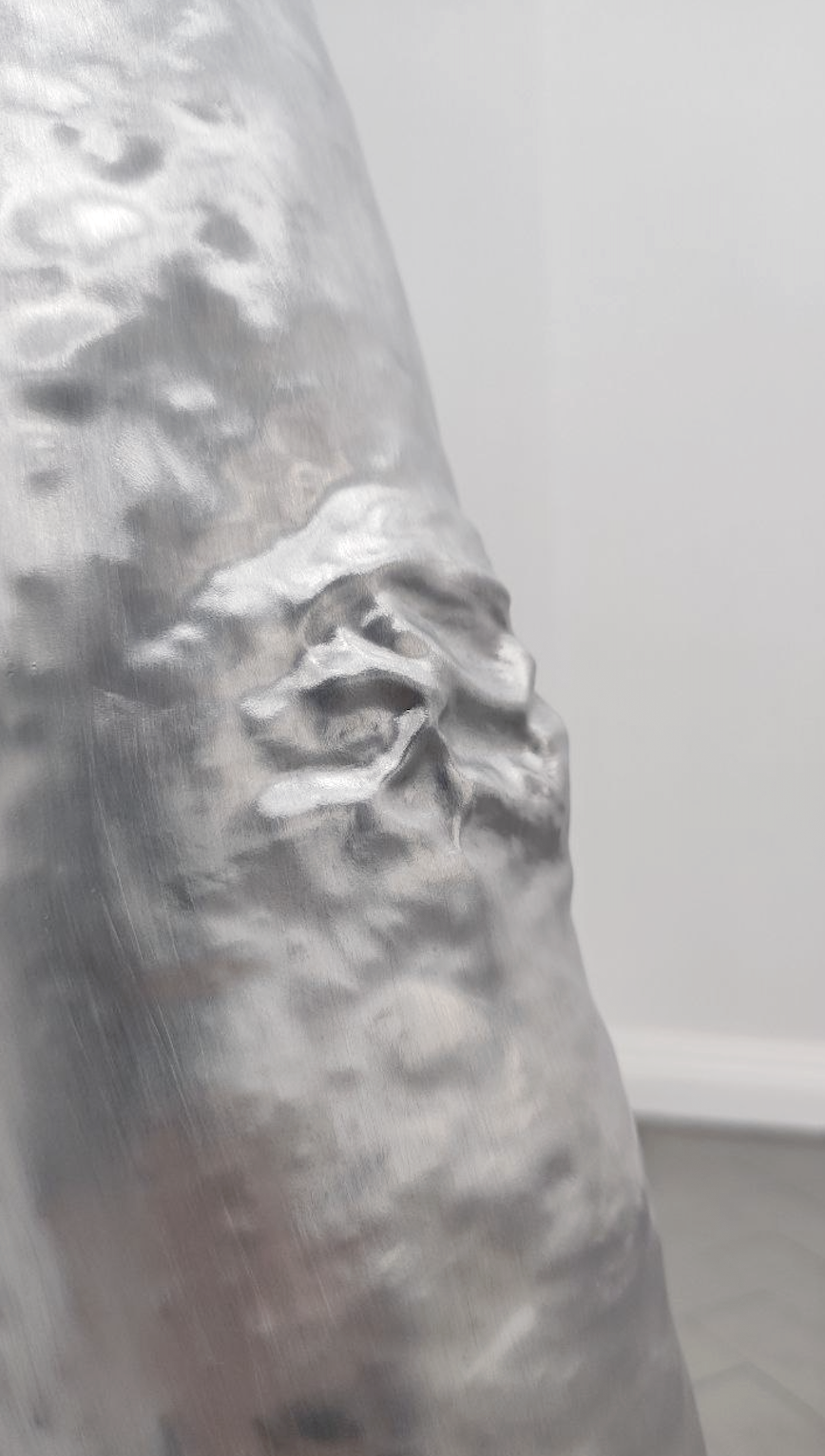

(…) To fathom [from the German Faden] the world, we embrace it with outstretched arms. We have always measured in spans of hands, feet and forearms, instrumenting our frailties to make the material world robust, containable, to make space yield. In addition to jost-ling away undesirables, or propping up one’s boredom, the Ancient Egyptians used the elbow as a vital measure: the cubit – the length of a man’s arm from his elbow to middle fingertip. The Great Pyramid of Giza was 280 cubits high. We have not ceased to extend our soft rulers and with a clenched fist hammer everything into shape. Upon a fall, the elbow fractures easily. (…)

(excerpt from a longer text by)

Ella Lewis-Williams

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

¹ Francis Ponge, ‘The New Spider’ in Things, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971, p.108.

² Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, London: Routledge, 2002, p.4.

³ The root of the word ‘text’ is literally „thing woven,“ from texere „to weave or braid.“

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / handmade aluminium sheet, 216cm x 10cm (left) / 216cm x 15cm folded (right) 3-pcs.

resilience forty-three point two / handmade aluminium sheet, 129,6cm x 10cm, 3-pcs., 6-pcs. / untitled (fracture II), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed

resilience forty-three point two / handmade aluminium sheet, 129,6cm x 10cm, 3-pcs., 6-pcs. / untitled (fracture II), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed

left: untitled (fracture II) right: untitled (fracture III), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed / 6-pcs

left: untitled (fracture II) right: untitled (fracture III), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, coloured pencil on Paper, framed / 6-pcs

untitled (fracture I), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper, framed

untitled (fracture I), EIGEN+ART LAB, Berlin, 2021 / 21x28 cm, Charcoal pencil on Sandpaper, framed